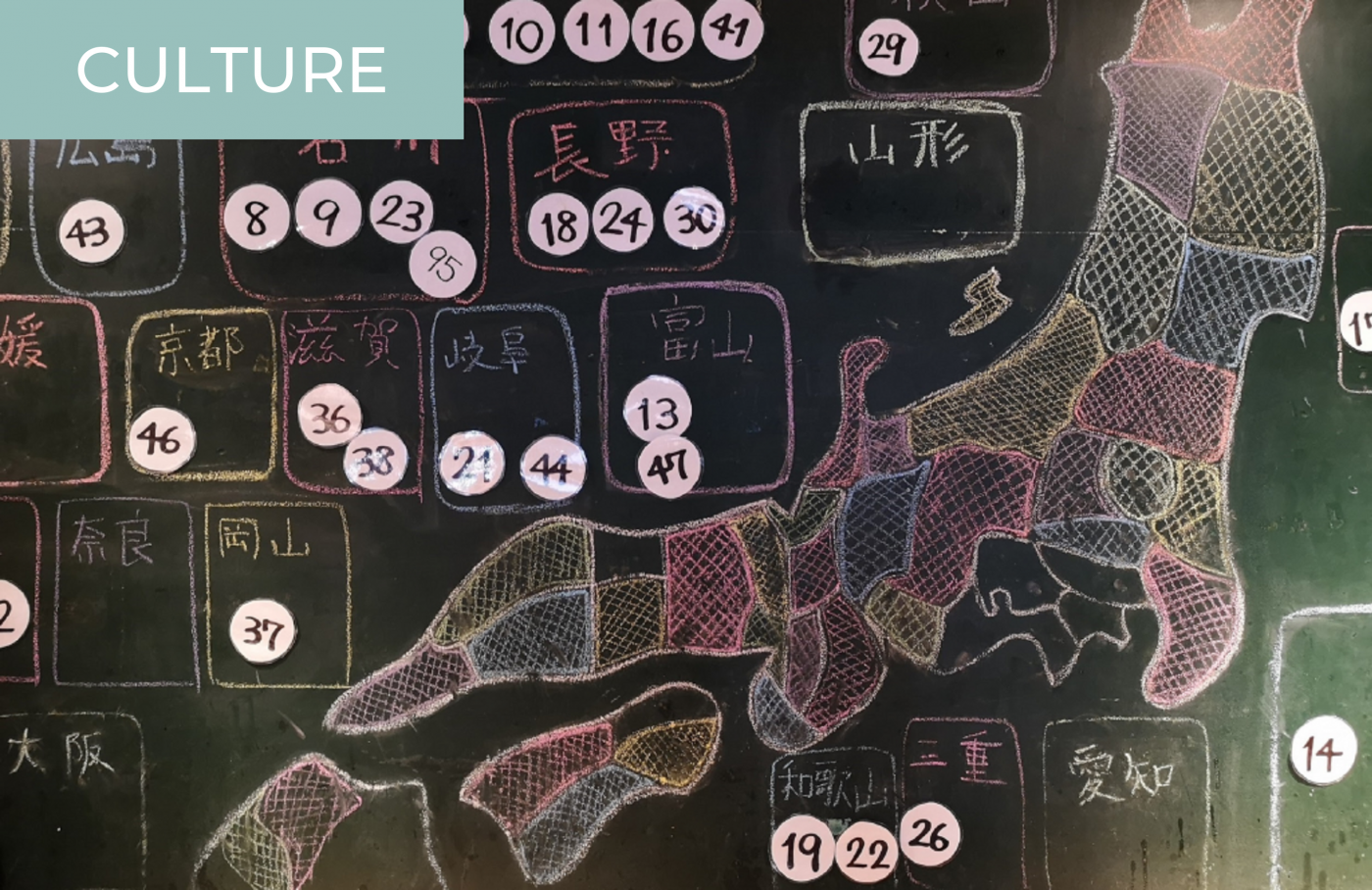

If you are interested in sake then it’s important to understand what factors can influence its taste. One factor is the place where it was brewed. Until recently, sake was mostly brewed and consumed locally, and thus acquired distinct regional styles. Sake brewed in different parts of Japan can vary in taste considerably. In this article, I will look at three ingredients that can change, when moving from one area to another. First, the type of rice, next, the kind of yeast, and finally, the water quality. Being familiar with the kanji of various prefectures will help you make an educated guess on what to expect from any sake, since this information is nearly always provided.

What is Sakamai, or Sake Rice?

First of all, it’s important to realize that rice used for eating is different from the rice used for making sake, which is called sake rice (sakamai 酒米) -it’s bigger and has a higher starch content in its core (shinpaku 心白), and less fat and protein on the outside. This is a key factor, because the main part of the sake process is the starch being turned into sugar, and then into alcohol. Fat and protein can spoil the taste and need to be removed through milling or polishing.

The local climate influences the growth of the rice grain, and thus the size of its starchy core. Since climatic conditions vary throughout Japan, with its long shape and many mountains, there are dozens of different varieties of sake rice. Over time, these tend to get replaced by newer varieties, so sake is a continuously evolving drink. Occasionally, a sake brewer may try and revive sake rice from the past, as was the case with the Kame no O (亀の尾) variety, the story of which was subsequently dramatized in the Natsuko no sake manga and TV drama.

Sake are determined by their region and its climate; sometimes these are mentioned on the bottle label. If the brewery chooses not to mention them, then the label will just say that the rice was domestically produced (kokusan 国産). In that case, knowing the prefecture where the sake was made, which is nearly always mentioned, could help you make an educated guess on the type of rice and the taste of the sake. Currently, only four kinds have achieved nationwide fame.

Four Famous Types of Sake Rice

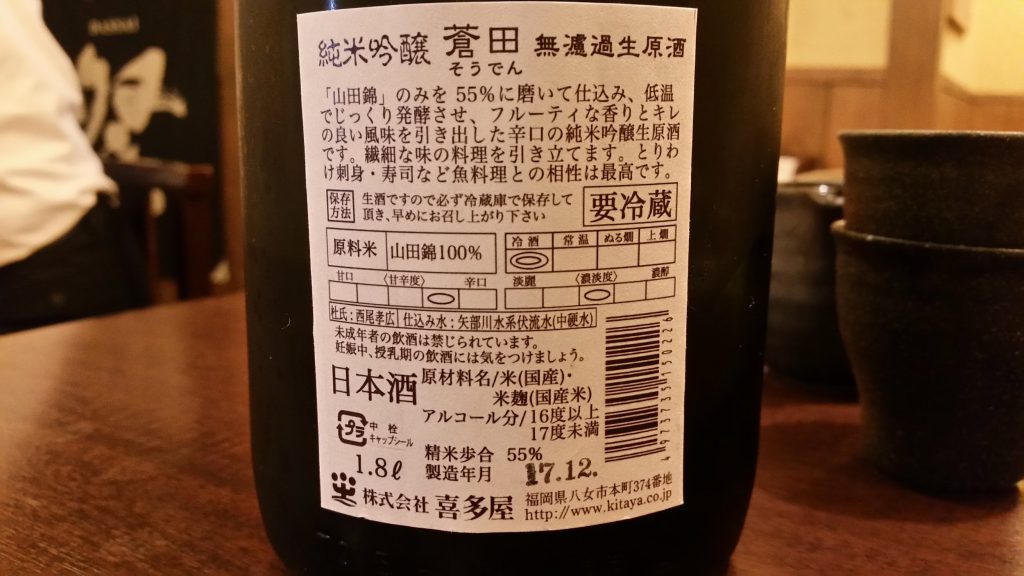

The one with the highest reputation is yamada nishiki (山田錦). If you have a chance to compare sake made from different sake rice, the one made with yamada nishiki will impress you most. The taste is full-bodied and savory, somewhat reminiscent of namazake (unpasteurized sake). It also has a pleasant, strong smell. It’s often used to make the highest class of sake. Although it can be cultivated anywhere in Japan, expect it to be used in sake from Hyogo, Okayama and Fukuoka prefectures.

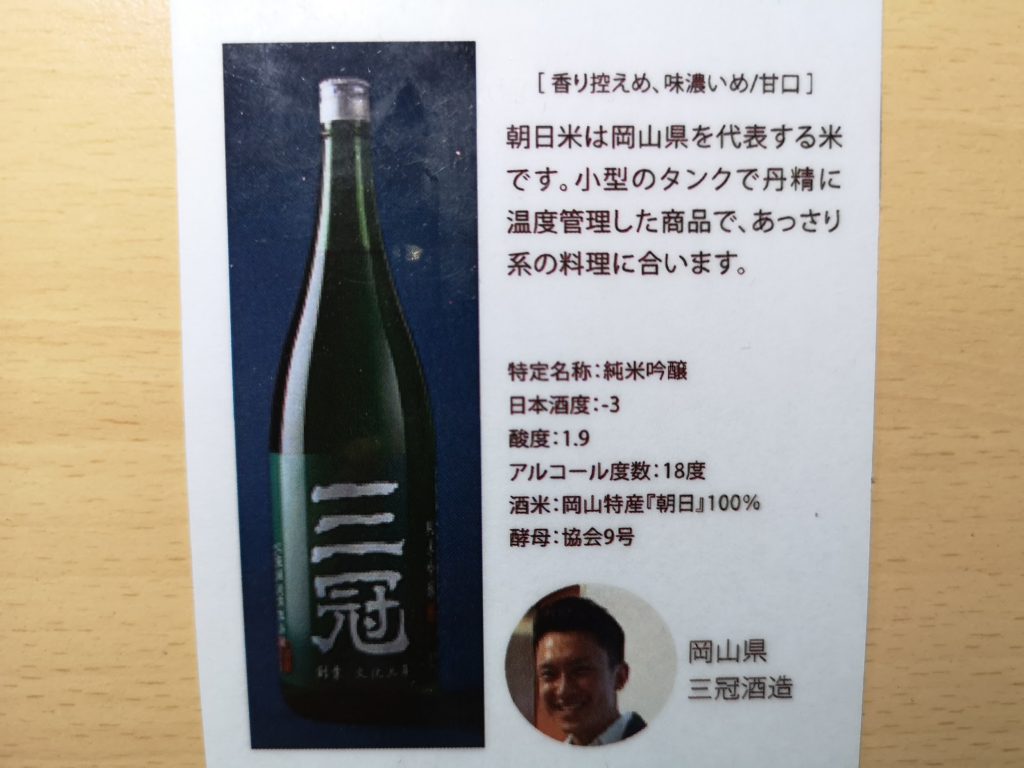

The second most famous type is omachi (雄町), from Okayama prefecture. It’s mainly famous for its long history – it was originally discovered in the middle of the 19th century, then abandoned after World War II, and was finally revived in the 1980s. It has a strong, unique taste, quite distinct from the above-mentioned yamada nishiki. I’m not a big fan of sake brewed from omachi rice, so if I’m out drinking sake, I tend to avoid Okayama ones. However, I’d definitely recommend trying it, especially if you prefer old-fashioned things to the mainstream.

The two next ones are more recent creations – they were developed through cross-breeding in postwar Japan and have a lighter, fresher taste. The first one is gohyakumangoku (五百万石) literally “5 million koku” (a koku is a unit of measure for rice or sake). This one is prevalent in Ishikawa, Niigata and Toyama prefectures. It is probably my favourite kind of sake rice, since it tends to result in a dry sake, with a sharp, clean taste.

The final one is miyama nishiki (美山錦), predominantly grown in Nagano, Iwate, Yamagata, and Akita prefectures. It has the lightest and most subtle taste of them all. It requires a cold climate in order to grow. As I mentioned above, there is a number of other varieties, mostly grown and used locally – if you’re able to speak some Japanese, why not ask what the sakamai is? It would be a great way to strike up a conversation about sake!

3 Main Strains of Yeast

Another main component is the rice yeast type (kome koji 米麴 or kobo 酵母), which is responsible for converting sugar into alcohol during the fermentation process. There are dozens of strains, with new ones being discovered and old ones being discarded on a regular basis. This work is done by individual breweries, and also by government-funded research centers. Somewhat less exciting is that, unlike the rice types, the strains aren’t given names, but numbers.

Because a strain discovered by a certain brewery will be used by that brewery, other nearby breweries, or perhaps even the whole region, it can also be characteristic of a certain area, since it strongly affects the taste. However, due to the ease of transporting strains (in a vial), it is not uncommon for certain ones to be used throughout the country. Let’s look at the most important types in numerical order.

Strain 7 was discovered by a brewery in Nagano and is the one most commonly used for making sake in Japan, due to its stability during fermentation. Strain 9 is another commonly used strain. This one became known thanks to a brewer in Kumamoto prefecture, in Kyushu, an area in Japan more known for shochu than sake. High fragrance is a key feature of this strain. It also tends to produce relatively dry sake. Completing the trio of most common strains is strain 10, developed in Ibaraki prefecture, and mostly used in Northeastern Japan, Tohoku. It produces sake that has low acidity.

It’s important to realize that the strain type is rarely mentioned on the bottle label. If you are curious to know what yeast strain was used to make the sake you are drinking, I would recommend visiting Sake Kurand Market. On top of being a great place for tasting and comparing sake from all over Japan, they provide detailed information for many of the sake in the form of small laminated cards that you are free to take home.

Hard or Soft Water?

Considering that sake is mostly made from water, let’s have a look at which of its components can affect the taste of sake favourably, and not so favourably. Originally, areas that had an abundance of high-quality water were the ones that became famous sake producers, such as Nada near Kobe. Knowing the area where the sake was brewed, tells us the type of water used and can give usclues on the taste.

Generally speaking, water containing a lot of iron and manganese can ruin the taste of a sake, whereas water rich in potassium, magnesium and phosphoric acid can help make a great sake. I’ll spare you all the chemicals details, but it suffices to know that finding the right water is crucial to making good sake. If the water doesn’t meet the requirements, it’s not unusual for a brewery to modify it artificially.

For tasting purposes, the most important quality is the hardness of the water. Hiroshima prefecture is known for its sake made from soft water, resulting in soft and sweet tasting sake. The same goes for the Fushimi, a major sake producing area in Kyoto prefecture, although the resulting sake tends to be drier. On the other hand, the aforementioned Nada in Kobe, Hyogo prefecture, uses hard water for its sake making it full-bodied.

Finally, water in mountainous prefectures located in Japan’s snow country, which receives an enormous amount of snowfall every winter, such as Niigata and Yamagata prefectures, have an amazing reputation, simply because the water there is believed to be extremely pure and rich in minerals. It’s probably the reason I’m partial to sake from these two prefectures. Also, perhaps, because I love mountains and hiking!

In conclusion, if you based in Tokyo, you’ll notice that sake is nearly always organised per region and per prefecture at restaurants and shops, so knowledge of each area can help you quickly find the sake that best suits your taste. If you are traveling throughout Japan, make sure to try locally brewed sake whenever possible – it will really help you expand your sake knowledge. In fact, you might even attempt to try sake from every different prefecture, something which I have yet to complete myself!

For a list of all the Japanese prefectures with Kanji, click below:

Japanese Geography: Japan’s Forty-Seven Prefectures