Have you ever been asked in a restaurant whether you wanted a shaku or ichigo? Have you ever worried about getting too much (or too little) to drink? Have you ever wondered, “How do I drink this?”? Japanese sake measurements can seem quite random and the reasons why are lost in time. However, if you look closely, a pattern emerges, which will make it easy to remember how much is what.

Ordering and Pouring

For the purpose of ordering in a restaurant, the smallest measurement is the shaku (勺), a traditional Japanese unit of volume, approximately 18ml. It shouldn’t be confused with its homonym the shaku which uses a different Chinese character (尺) and is a traditional unit of distance (approximately 30 cm). If you just want to have a taste of the sake, then this is the perfect choice. Just bear in mind that it’s one third of a serving of whisky, so you will only be getting a sip or two.

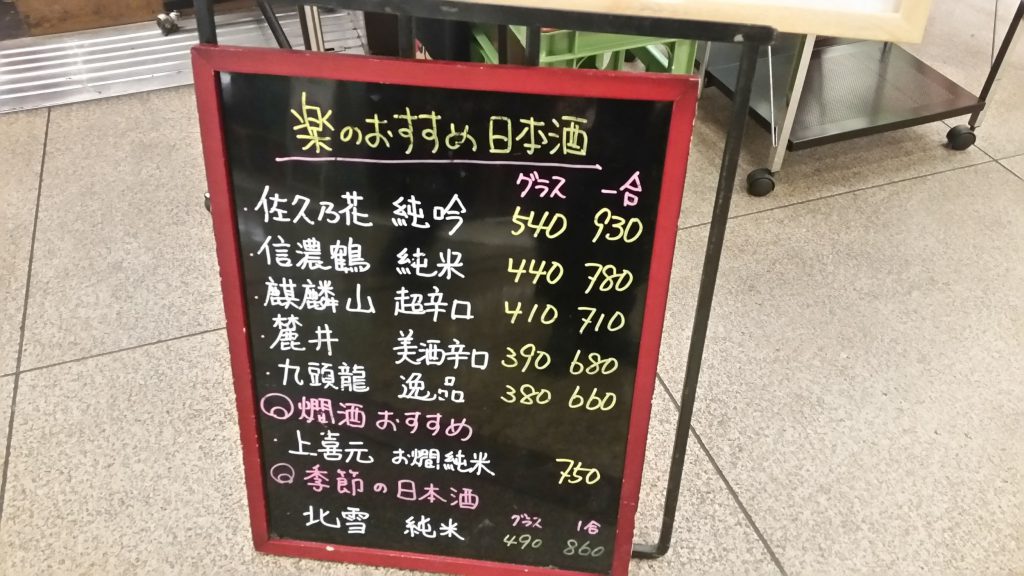

The next serving size is a gurasu (グラス), the Japanese word for glass (usually 110ml). However, if you have more confidence in your selection, then go for a go. One go, or an ichigo, (一合) is ten shaku or approximately 180ml. It’s similar to the Japanese word for strawberry, except that the last “o” is long. It can be served in two different ways. The first way is to pour the sake into a glass sitting inside a masu (升), a 160ml square wooden box, until the sake (about 20 ml or a little over a shaku overflows into the masu.

This traditional way of drinking sake is fun and presents its own unique challenges. First, when drinking from the glass, be careful not to drip sake over yourself, since the bottom of the cup is wet. When the glass is empty you can either pour in the remainder from the masu, or drink directly from the masu itself. Its square sides can make both actions tricky, especially if this isn’t your first drink! The masu gets its shape from the fact that in medieval Japan it was used for measuring rice.

The second way to drink an ichigo is to have it served in a small bottle or tokuri (徳利) and a small cylindrical cup or ochoko (オチョコ) both made of ceramic. In case you plan to share the sake, you can ask for two or three ochoko – just use your fingers to indicate the number. Coincidentally choko is also the Japanese word for chocolate, although due to the context, there is no chance of getting some! If you ordered hot sake or atsukan instead of cold or room temperature sake, this is how it would be served. Just remember that you’ll need to pour your own cup and those of your drinking companions – the tipsier you get the trickier! Incidentally, the “one cup sake” that you can buy in most convenience stores is also one go…for drinking “on the go”.

An ichigo will usually fill three cups – hardly enough for a party of 4 or more people. Ordering nigo, meaning two go, will get you two tokuri bottles or 360ml in total, and sango, meaning three go, three bottles or 540ml. At this stage, you might consider ordering a whole bottle which is four go or 720ml. Isn’t it wonderful when everything adds up nicely? For comparison, a standard serving of wine is 175 ml and a bottle is 750ml (times 4.28); a glass of beer is 330ml and a bottle is also 750 ml (times 2.27). This also means that it’s best to share a bottle of sake between two or four people.

Sake Bottles, Barrels and Breweries

Continuing to look at bigger sizes, we notice that the number 18 comes up again and again. Let’s imagine you liked the sake you had in the restaurant so much that you wanted to buy an extra big bottle to share at the next home drinking party. In that case, you’ll need to purchase an ishobin, meaning a one sho (升) bottle, which is approximately 1.8L or 10 go. Confusingly, it’s the same character as for the wooden container masu – the first is the Japanese reading, the second is the Chinese one. Sake Bars and some restaurants will typically serve sake from one sho bottle.

Going further, ten sho equals one to (斗) or 18L – are you still following? – which by itself isn’t used very much. However, four to, or 72L, is equivalent to the amount contained in a barrel or a taru. You may have noticed these (empty) sake barrels displayed in stacks at shrines. Unlike wine and beer barrels, they’re coloured white and covered with beautiful designs. After that, the next unit of measurement is the koku (石- same character as for stone). This is a measure for ten to or approximately 180L.

The koku was originally a unit to measure rice – the amount a person living in Edo Japan could eat in a year – it is now used to measure production levels of a sake brewery. There is a famous variety of sake rice from Niigata prefecture called gohyakumangoku (五百万石) meaning five million koku or 900 million liters of sake. The name refers to the maximum yield of its first year of cultivation – it was officially named only 20 years after its discovery in 1938!

The Mysterious Number 18

So, obviously, the number 18 seems to be a big deal. But why was it originally chosen as a unit of measurement for rice and liquids?And why is it still used in modern sake production today? The answer to the first question is quite difficult – in fact it may not have an answer at all! Like many mysterious things in Japan (“kanji”, buddhism…), these measurements were originally brought over from China. Over time, many regional variants appeared but they were all unified into one system under the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868). Since Japan was isolated from the rest of the world during that period, the metric system never stood a chance.

This doesn’t resolve the puzzle as to why such a random number was chosen in the first place. The metric system is based on ten, simply because we have ten fingers. However our time system is based on the number 12 – a legacy of the Sumerians and the Babylonians – and also seems very random, except when you consider that the number 12 can be divided in four different ways (by 2, 3, 4 and 6). This makes it quite useful for making time divisions.

Actually, the number 18 can also be divided in four different ways (by 2, 3, 6, and 9) so this could be the reason that it was chosen for sake measurements, especially when you consider that many of these measurements were also used for rice. For example, if you had 18 liters of rice, you could divide it into halves, thirds, sixth, or ninths. For comparison, the number ten can only be divided in two ways. If you had 10 liters of rice, you could only divide it into halves or fifths – not very practical at all! So although this isn’t the official reason, it is a very plausible one. Admittedly, they could also have used the number 12 but then there would be less sake to drink in our cups!

The answer to the second question is relatively easier. Since sake is considered a traditional beverage, it follows that it should be brewed using traditional methods and measurements. As long as the majority sticks with this opinion, sake will continue to be produced and served in shaku, go, sho, to, and koku. Finally, I forgot to mention that there is a unit even smaller than a shaku mentioned at the very beginning of this article. It’s a sai or 1.8 ml – possibly the sound one would make if served such a minuscule quantity of sake!