Did you know that Japan has been a multi-ethnic country since its inception? If your response is “no,” you’re not alone. Apart from the Yamato (the dominant ethnic group in Japan, often just known as “the Japanese”), there are three other indigenous ethnic groups in Japan: the Ainu, the Bonin (also known as the Obeikei), and the Ryukyu (also known as the Okinawans). In this article, I’d like to share with you more about the Ainu people, whom I have had a deep interest in since my university days.

Despite taking Japanese language and culture classes for years in both the US and Japan, I only first learned about the Ainu from diving through a series of related pages on Wikipedia. My ignorance was not unique; just in 2020, the then-Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso drew criticism for asserting in a speech, “No other country but this one has lasted for as long as 2,000 years with one language, one ethnic group, and one dynasty.” In fact, despite their rich culture separate from the Yamato and centuries of documented history, the Ainu were only officially recognized as an indigenous group by Japanese law in 2019. So who are the Ainu, and what’s going on?

Who Are the Ainu People?

The Ainu are a collection of indigenous peoples who mostly settled in modern-day Hokkaido, northern Honshu, and the Russian islands around the Sea of Okhotsk before they were colonized by the Japanese and Russians. Series of genetic research has not connected them directly with any other modern ethnic group, although they do share genetics with the Ryukyu, Yamato, and certain indigenous groups in Mongolia, Siberia, and North America.

The current Ainu population in Japan remains unknown. Depending on counting methods, estimates vary wildly, from only about 20,000 to 200,000 total, or only a few hundred for “pure” Ainu who don’t have mixed heritage.

What Is Traditional Ainu Culture Like?

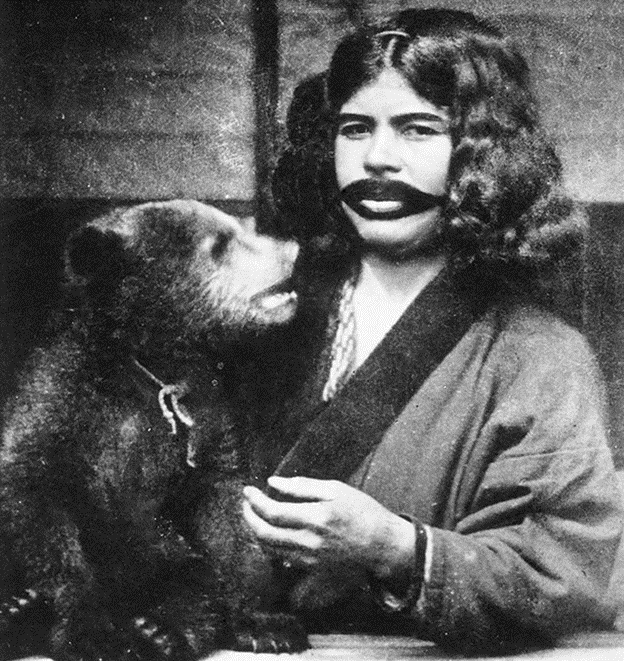

The Ainu language and culture are distinct from Yamato culture and share many characteristics of other indigenous cultures from Northeast Asia and North America. For the majority of their history, the Ainu were hunter-gatherers, primarily fishing salmon and trout and hunting bears and deer. Unique from many other hunter-gatherer societies, they usually settled in fixed locations with superb river access. Their small settlements were called kotan in the Ainu language and were usually characterized by a few thatched-roof houses, a hepereset, or a hut to keep young bears that were usually sacrificed in religious ceremonies, and facilities to preserve food and animal skins.

Strikingly different from Yamato culture is their tattoos. While mainstream Japanese society largely stigmatizes tattoos, they are important aspects of Ainu tradition. Girls gradually tattooed their faces and sometimes their arms and hands over years to mark their entry into womanhood.

On the other hand, the Ainu were traditionally animists, believing that everything in nature is host to a kamuy, or spirit, which has some overlap with Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion in this regard. Distinctly, most crucial to the Ainu religion are the spirits of the hearth, bear, and sea, pillars of Ainu livelihood. Spirits are regarded as immortal, and when an animal host dies, the spirit is sent back to the land of the gods. This is why Ainu traditionally thanked the spirits before meals and engaged in ritual bear sacrifice, the body from which they then made tools and meals.

Why Did It Take So Long to Acknowledge the Ainu?

As with many indigenous peoples around the world, at the root, generations of nationalistic politics are to blame for the disregard toward the Ainu.

Although interactions between the Yamato and Ainu had been documented for centuries, it wasn’t until the Edo Period (1601-1868) that relations accelerated, largely in the form of trade. Until the late 18th century, commerce was booming between the two. Although there were many benefits for the Ainu by doing business with the Yamato, this period still experienced occasional rebellions against the Yamato’s expanding political power and outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases.

The end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th marked a horrific turning point for the Ainu. As Yamato colonizers pushed further into Hokkaido, the Japanese government began genocidal practices against the Ainu. Ainu women were forcibly separated from their husbands and endured systematic sexual and domestic violence by Yamato men, with Ainu men trafficked for labor. Epidemics against which the Ainu had no or little immunity further decimated the population. While there were an estimated 80,000 Ainu in the 1700s, by 1868, less than 20,000 remained.

Under the subsequent Meiji regime (1868-1912), the Japanese government officially annexed Hokkaido, and policies against the Ainu expanded. Apart from taking their land away and distributing it to Yamato colonizers, the Japanese government banned the Ainu language, tattooing, and religious practices as well as deer hunting and salmon fishing, which were integral to their livelihoods. They implemented forced assimilation with the Yamato people to erase Ainu culture.

Japan’s politically-induced social amnesia toward the Ainu gained new ground after World War II. After Japan’s multiethnic empire fell in 1945, subsequent governments asserted a new social consciousness, promoting Japan as an ethnically and culturally homogeneous country, and thereby creating a new “united” Japanese identity.

What Is the Situation of the Ainu Today?

In modern-day Japan, the Ainu still face a lower standard of living compared to their Yamato counterparts. Today, it is still difficult to ascertain the actual number of Ainu people in Japan, as many have intermarried with Yamato Japanese people and/or wish not to be identified as Ainu; due to the generations of persecution and Yamato stereotypes viewing them as barbarians, many Ainu have long feared identifying themselves. Ainu activism particularly started surging in the 1980s but with limited success; however, the turn of the 21st century has been marked by another wave of activism challenging the Ainu’s second-citizen status and the idea that Japan is a monoethnic society. Particularly after the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, civic and political movements in Hokkaido gained momentum in their efforts to recognize, protect, and give reparations for the Ainu.

How Can You Learn More About and Support the Ainu People?

Luckily, with more national and international attention, there are many resources and experiences to let you engage with Ainu culture. Feel free to leave us a comment if we are missing any of your favorites!

Ainu Language Resources:

- Drops: Ainu (App)

- アイヌ語ラジオ講座 (Podcast)

- Memrise: Complete Beginner’s Ainu

- Ainu for Beginners (5 lessons)

- しとちゃんねる (YouTube)

- 公益財団法人 アイヌ民族文化財団 (Multimedia)

Ainu Restaurants:

- HaruKor (Tokyo)

- Umizora no Haru (Sapporo)

- Poronno (Akan Mashu National Park, Hokkaido)

Ainu Museums and Cultural Centers

- Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park (Shiraoi, Hokkaido)

- Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples (Abashiri, Hokkaido)

- Multiple Ainu museums and villages (Akan Mashu National Park, Hokkaido)

- Kawamura Kaneto Aynu Memorial Museum (Asahikawa, Hokkaido)

- Sapporo Ainu Cultural Center (Sapporo, Hokkaido)

- Tokyo Ainu Cultural Center (Tokyo)”

Ainu Cultural Tours and Experiences

- Anytime, Ainutime outdoor and cultural experiences (Akan Mashu National Park, Hokkaido)

- Guided Ainu hiking and cultural tour (Asahikawa, Hokkaido)

Ainu in Popular Culture

- Golden Kamuy (Manga and anime series)

- Ainu Mosir (Film)

- Princess Mononoke (Film) – Although it is not explicitly mentioned by Ghibli, multiple characters seem to be inspired at least in part by the Ainu.

———————————————————————————————————————

Other sources:

https://archive.org/details/conquestainuland00walk

https://daisetsu-kamikawa-ainu.jp/en/story/kinenkan/

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/japan/ainu.htm

Maher, J.C. “Akor Itak-Our Language, Your Language: Ainu in Japan.” Trans. Array Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Joshua A. Fishman. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 2001. 228, 330-331, 333, 337-338, 341, 345.

Martin, Kylie. “Aynu itak : on the road to Ainu language revitalization.” Media and Communication Studies. 60. (2011): 58, 67, 71-72, 74-76, 77, 79, 81, 84-85. <http://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/handle/2115/47031>.

Teeter, Jennifer, and Takayuki Okazaki. “Ainu as a Heritage Language of Japan: History, Current State and Future of Ainu Language Policy and Education.” Heritage Language Journal. 8.2 (2011): 96, 100, 104-106.

One Comment

Faye Smith

August 22, 2023 at 7:38 PMTo your knowledge, has there been a study comparison between the Ainu Cultural decimation in the 1800’s and the the attempted cultural destruction of the indigenous Native Americans in the USA in the same time frame?