Before I went to Japan for my first time as an exchange student, I believed the generalization that Japan is extremely healthy and that I would lose several pounds by not even trying. Although I spent my normal weeks walking to class every day around my massive American college campus, generally eating healthy meals, and taking Zumba classes at the gym multiple times, I was under the impression that somehow Japan would work the magic that my American life did not.

After just a few weeks into my stay in Japan, I was shocked to realize I had to try to make sure I didn’t gain weight. With my host family, I was fed processed white bread for breakfast and served heaping portions of white rice or noodles for lunch and dinner. My afternoon snacks of fruit or dairy were replaced by packaged cakes and candies since fruit is more expensive in Japan. I walked 20 minutes to the station and 10 minutes to campus twice a day, and that was all the movement I generally did. I struggled with the best ways to stay healthy in my daily life.

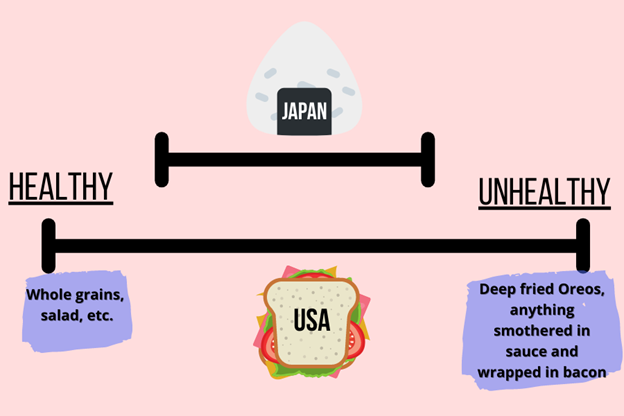

“Japan is healthy” isn’t necessarily a lie. Compared to many other countries, and especially the US, healthcare in Japan is extremely affordable, and it’s easy to see a doctor. “I lost so much weight in Japan!” is also very true for many people. But it’s a very subjective reality. What I came to realize is that on the spectrum of healthy and unhealthy, America has two vastly different extremes, with myriads of whole wheat/grain options and salad bars on the one end, and deep-fried Oreos on the other.

In contrast, generally, Japan has a much more limited scope that fits somewhere in the middle. Portions do not tend to be as massive as in the US, but I have been served many enormous bowls of ramen and plates of omuraisu that I really wished I could take home half of (doggie bags are generally not options in Japan). Fish is generally the staple meat, and there are some non-animal-based proteins like tofu and natto, although consumption of red meat is increasingly common. Japan does have quite a variety of fried foods (karaage, tempura, tonkatsu), but vegetables are often integrated into cooked meals more than they tend to be in the US.

On the other hand, white, processed carbohydrates tend to be the focus of most Japanese cuisine (brown rice is for only “extremely health-conscious mothers or vegetarians,” I was told). Bakeries are also everywhere, making it tempting to indulge in more carbs. Therefore, whether Japan is “healthy” completely depends on what your lifestyle and diet were like at home.

So, especially if you lean to the left of the diagram, how can you take care to eat healthy meals in Japan? I follow three rules.

Rule #1: Avoid building a habit of over-indulging in local treats.

Especially when you move to a new country, the novelty factor makes it easy to overeat certain foods (for me, it was melon pan). When I returned to Japan after graduation, I overindulged in the pastries at the convenience stores and bakeries because it had been so long since I had any. Before I knew it, what I had originally planned to be a treat after a long while had turned into a habit. Break your bad habits early. Sure, matcha Kit Kats are amazing, but if you buy them, put them in a place (corner of a cabinet, drawer, etc.) that’s not somewhere you look immediately, because the phrase “out of sight, out of mind” is true to an extent. Eat your sweet (or savory) kryptonite every now and then, but make sure it’s not regular enough to form a dependence or a habit.

Rule #2: Particularly watch out for the convenience store food.

This is essentially one form of Japanese fast food in that it is cheap and pretty delicious, but can be immensely unhealthy. Just like how you can order healthier options at American fast food establishments, you can buy oden, salads, or other health-conscious meals at convenience stores. Or you could order pork buns, corn dogs, spaghetti and meatballs, omuraisu, katsudon, okonomiyaki, etc. Some of the set meals offered can be 1,000 calories by themselves. Conbini food is cheap and pretty good quality, but just watch out. As always, also watch out for eating too much at places like Yoshinoya, Coco Ichiban, and other fast-food chains.

Rule #3: Find healthy substitutes.

While I was in Nagoya, I managed to find whole wheat spaghetti in the import stores and one variety of brown rice in the rice section of the regular grocery stores. However, I found neither of these in any local or international stores when I moved to Utsunomiya. If they were supplied, the prices were exuberant. For these, as well as many other foods from back home you can’t find too often, such as oatmeal or almond butter, Amazon and Rakuten are your friends. Online you can find giant bags of brown rice for reasonable prices, often with free shipping or discounts for regular purchases.

As for whole grain bread, while you will definitely not have the same amount of choices as you probably would back home, if you look hard enough, you can find about one or two choices of bread containing whole grains or the sort in the aisle packed with thick, white, processed bread. While these still may be on the unhealthy side compared to what you eat back home, they’re usually the better options of the mass-produced varieties.

Also, if you don’t want to pay the price for the comfort of home and health, find some substitutes with Japanese ingredients! I’ve found varieties of “ramen” in supermarkets with noodles made from konjac, which is packed with fiber and low in calories. Instead of buying overpriced wheat spaghetti, substitute your Western noodles with soba (buckwheat noodles). Get creative with your cooking, and the world opens up to you.

Key Japanese Words

Finally, when searching online or at the market, here are some words to look out for:

低糖質 (tei toshitsu) or 糖質オフ (toshitsu ofu): “low-sugar” or “reduced sugar”

低カロリー (tei carorii) or カロリーオフ (carorii ofu): “low-calorie” or “reduced calories”

低脂肪 (tei shibo) or 無脂肪 (mushibo): “low-fat” or “nonfat”

全粒 (zenryu): whole grain

玄米 (genmai): brown rice (as opposed to “white rice” or 白米 [hakumai], which is standard and probably won’t be labeled specifically)

こんにゃく、コンニャク、 or 蒟蒻 (konnyaku): konjac

Before ending, I want to note how important it is not to only connect “healthiness” with “thinness.” When compared with my Japanese friends and coworkers (and I can give many anecdotes), it often turned out I tended to eat healthier and exercise more, yet I was never at the same thinness as them. Surely part of it is genetics as well, and want to stress to avoid equating “healthy” with “thin.” Listen to your body, and find your best ways to eat healthy meals in Japan.