They sit in their tiny rooms, in front of their computers, and lie on their beds during the day. They only go outside at night, and only if they can’t avoid it. Out into life? No, not at all. For these young people, life takes place in a few square meters. It is a life of self-imposed isolation – for months, years, sometimes decades. They are called hikikomori, which is derived from the Japanese word for “retreat.”

This article was kindly provided to Kokoro Media by our partner, the German-Japanese Association in Munich (Deutsch-Japanische Gesellschaft (DJG) München), and was originally published in the association’s newsletter, Kaiho July/August 2022. The article was originally written by Martin Thurau (LMU research editor Einsichten. Das Forschungsmagazin) and published in the LMU research magazine Einsichten, issue number 2 / 2021. Translated from German to English for Kokoro Media by Jeanne-Rose Therre-Ohlig.

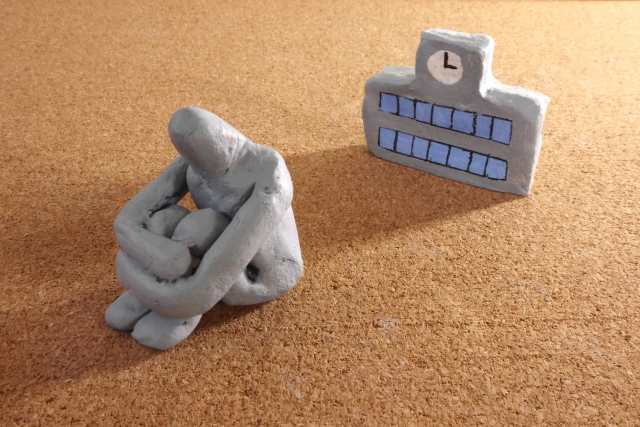

Always in the Room: There Are Hundreds of Thousands Who Lose the World At a Young Age. The Japanologist Evelyn Schulz On the Phenomenon of the Hikikomori.

Usually, the hikikomori still live with their parents, but they avoid contact with them too. In Japanese TV films, explains Evelyn Schulz, for a long time, a few images were enough to describe the situation sufficiently for every viewer: the closed room door in front of which the mother puts the food down. “That is a fixed trope. “

According to the professor of Japanese studies at the LMU, this alone shows how widespread the phenomenon is in Japan. As early as the 1980s, Schulz recalls, her host family at the time reported such cases “of people who were afraid of the world, perhaps depressed and struggling with diffuse mental disorders .” In the meantime, experts estimate that in Japan alone, there are between half a million and more than a million people, mostly men, who lose their connection to the world in this way. Nobody knows how high the number of unreported cases is.

Even though researchers now believe that similar phenomena exist in other countries, the sheer number of people affected in Japan is astonishing. What drives young people into isolation? What makes withdrawal a mass movement? What peculiarities of the Japanese social structure have contributed to this? According to the official definition, someone is considered a hikikomori if they isolate themselves from the world for more than six months. But otherwise, the diagnostic criteria are far from uniform. The circumstances and life stories of those affected are diverse and do not form a uniform pattern. Dysfunctional family structures, childhood traumas, bullying experiences, failed school careers, problematic love relationships – different reasons can be the trigger. For many of those affected, withdrawal is accompanied by mental disorders. The list of comorbidities is long: schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, etc. But in most cases, it is not yet really clear whether they are the cause or not, rather the consequence of social withdrawal.

The Burden of the Right Career

“In Japanese society, there are very normative ideas about what educational and employment biographies should look like,” Evelyn Schulz outlines. And when many parents have only one child, they like to concentrate all their wishes for prosperity and advancement on this one child and overload it with exaggerated expectations.

“The school system is very rigid,” says Schulz. “School, it’s still like that today: children have classes all day, and in the evening, they go back to a private cram school.” To get into one of the good secondary schools or a renowned university, young people have to pass tough tests. And unlike in Germany, for example, Schulz says, there are few dropouts in this system: those who don’t make it have often gambled it away.

“I saw that a lot during my visits. I wondered how the children could stand to have so little freedom.” And where the social biotope is a monoculture, those who don’t want to grow so straight have a hard time: “Often it’s not even the failure of the school requirements,” says Schulz. “Often the young people just don’t fit into that system.”

The socially prescribed career grids are narrow. Even those who want to do a year abroad after graduation risk no longer fitting into the standardized CVs. For a long time, this functioning according to rigid rules was even considered promising: if you work hard, it was said, you will make it – a kind of turbo variant of the German economic miracle mentality. Furthermore, social recognition and social status are still more strongly linked to a straight career than in hardly any other country.

But this imaginary business model of the post-war era no longer has a secure foundation in times of globalization and post-industrial upheaval. Even though Japan is still the third largest economy in the world and the yen is a very strong currency, the old promise of prosperity no longer applies. Japan has become a divided society in which the social gap is widening, and the middle class is crumbling.

All this does not make it easy to find one’s place in society. However, according to Schulz, more and more young people are turning away from the rigid collective performance ethic and from the patriarchally organized professional world and are striving for other forms of life and work. Some are founding small start-ups, and others are shifting down a gear professionally and looking for a work-life balance. “And in the meantime,” says Schulz, “parts of society are also showing more understanding when someone says: I can’t anymore, I don’t like anymore, I can’t keep up anymore.

The Culture of Shame

This Japanese variant of refusal has nothing demonstrative about it; it is directed entirely inwards. It is not a loud protest but a silent disappearance from the outside world. In reports, those affected speak of being considered “failures” in the conventional sense; they speak of their guilty conscience because they are still living at their parent’s expense. Most hikikomori, says Schulz, see their situation very clearly. They know that with every month, with every year, their chances of getting back on their feet dwindle. But many have settled frugally into their shadowy existence.

And the families? “The whole thing is very shameful,” says Evelyn Schulz. “How are you supposed to deal with having someone in your family who is not who you think they are?” That, too, is a stigma. And yet Japan is “a society that gives space to deviance, even if it’s in private. People just let the hikikomori be, that’s the way it is. Of course there is shame, of course there is helplessness”.

The word hikikomori reflects this ambivalence, says the Japanologist. It describes a massive social problem almost in ironic refraction with a term that radiates something positive, even something cozy: “I withdraw.” And it protects against further questions. “With this term, everyone knows what is meant. People don’t ask further questions.” Because in Japan, people don’t usually talk openly about mental problems. At any rate, I have experienced it only rarely, mostly only among close friends,” says Schulz. Going to a therapist is anything but a given. And so it takes a long time for those affected or their relatives to seek help. In the meantime, however, there are many contact points that offer counseling and support for parents and try to bring hikikomori out of isolation with low-threshold offers.

The Problem of Ageing

Japan today is considered a “super-aged society.” At 48.4 years, the country has the highest average age of its population worldwide. Almost 30 percent of the inhabitants are 65 years and older. Evelyn Schulz remembers her last visit to the country: “A friend showed me rows and rows of former primary schools that had been converted into homes for the elderly. Mind you, this was in Greater Tōkyō, in the direct catchment area of the megacity, not in the outlying areas.” According to the Japanologist, the aging of society is the dominant social problem.

Like society as a whole, the hikikomori have long aged. Surveys show that their numbers in the over-40 age group will soon be as large as those below. Some of them have been living in seclusion for decades with their now elderly parents, who still support them financially. “Often, it is only when both parents have died that it becomes clear that someone else is living in the house. But middle-aged hikikomori are also growing up. Surveys of 40- to 65-year-old sufferers showed that many of them only fell into social decline in later years, whether through mental health problems, other periods of illness, or job loss.

What role does increasing digitalization play in all this? One might suspect that the connection to the virtual world exacerbates the problem. In fact, many hikikomori are considered internet addicts according to the usual criteria. The net makes it easier for them to avoid social contacts in the real world, which are confusing and frightening for them. It creates communication for them – under its conditions, the risk of failure is subjectively perceived as lower.

But can’t the internet also be part of the solution? Some hikikomori, says Evelyn Schulz, have successfully developed social activities on the internet, for example, in self-help or as bloggers. But at least it opens “a window into the closed world of hikikomori” – not least for therapists, doctors and other members of the help system. And what sounds a bit bizarre in this context: even a game like Pokémon Go has allegedly brought some sufferers back onto the street because they suddenly had to score points in the real world.

The fact that more and more young people everywhere are immersed in digital worlds is also one of the traces that links the hikikomori syndrome to similar phenomena in other societies. A number of studies have found clusters of extreme social self-isolation in Spain, the USA, South Korea and India, among others. Therefore, some researchers now warn that hikikomori is a phenomenon that does not only affect Japan, but could be linked to modern societies in general.

Prof. Dr. Evelyn Schulz researches and teaches at the Japan Centre of the LMU. Schulz, born in 1963, studied at the University of Heidelberg and in Kyōto, received her doctorate in 1995 and habilitated in Japanese Studies in 2001. From 1995 to 2002 she was an assistant and senior lecturer at the East Asian Seminar of the University of Zurich before being appointed to the LMU in 2002.

Top Image Credits: Hikimori 2004 by Francesco Jodice