As three authors from three different countries, we all share one common thread. We’ve all achieved a working knowledge of Japanese, and each of us has done so in our own unique way. There’s no single “right” way to learn Japanese, and in this article we hope to give you a few ideas that you can use to chart your own Japanese learning journey.

Origin Stories, Tests, and Textbooks

Anthony: I’ve been studying consistently for more than 10 years—basically since I arrived in Japan. But before that, I briefly studied Japanese at different points in my life. For example, when I was in college, I took a year of Japanese to fulfill the language requirement for my business degree. For our readers who are thinking about studying Japanese, I recommend this kind of formal structure, at least for the first year. Having classmates and being forced to write all of the kanji characters made for a great foundation.

Here in Japan, I took private lessons for nearly eight years. This was great because I could customize the lessons to the needs of my daily life. During that time, I used a lot of textbooks that you can find in Tokyo bookstores. Eventually, I realized that the most effective way for me to learn the language was working for a Japanese company, using Japanese every day to do my job. Also, using flashcards with good spaced-repetition algorithms helped a lot as well.

Amelie: I started learning Japanese during my last year of high school. At that time, I liked reading Japanese manga, and I was becoming interested in Japanese culture. My best friend and I just started learning Japanese for fun. But in the city we were living in, there were no Japanese classes. So we just bought this book that was called something like 40 Lessons to Learn Japanese. There were very few books to learn Japanese via French at the time. This one was actually very good. It taught the language little by little with daily lessons. I could learn a little bit of vocabulary and grammar at the same time, but at a very slow pace. However, after the 40 lessons, you know the basics of grammar. Concepts that are typically difficult for Japanese learners are well explained in the book.

After that, I went to university and studied something completely different: English. However, I made one Japanese friend who was a foreign exchange student. I tried my very poor Japanese on her, and she then taught me some new things in response. I picked up more vocabulary and more grammar, but I still couldn’t write.

Eventually, I had the opportunity to live in Fukuoka for about a year. There I could pick up even more vocabulary and talk more. I also took Japanese lessons and did a little bit of kanji writing. At this point, my teacher told me that I should take the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) upon returning to France, since I had achieved some level of proficiency. So when I went back to France, I studied for the JLPT and learned to read—but not write—more kanji.

I passed JLPT N2 in 2007 and returned to Japan in 2011. Because I spoke Japanese at work, I had to learn a lot of new things, and after some time, I realized I was unconsciously improving. Working did a lot for me because I had to speak in Japanese every day from morning to evening.

Now my main problem is that I can speak, read, and follow meetings in Japanese, but I cannot write kanji. So if you want to reach a good overall level, taking classes is probably the best option because you will have to write what you are saying. I didn’t get this. I didn’t have the structure. I learned everything on the spot and by talking with people. So, I might not be a very good example of what you should do [laughs].

Anthony: I wouldn’t say that. Writing isn’t necessary these days. You need to learn how to type—that’s for sure. But I don’t emphasize writing anymore. After the first few hundred kanji characters, I stopped worrying about writing them. Once you start working in Japan, you don’t write. You just type. I’d love to come back to writing someday—maybe when I’m retired and I can enjoy it as calligraphy or something. As for now, reading and other aspects of the language are more important to me.

Amelie: Well, sometimes I have to write memos on Post-it Notes. Occasionally I don’t know how to write the kanji characters I need, and I have to look them up on a computer. I’m a little ashamed to have to do that.

David: Writing comes up in unexpected places—going to the doctor, for example. Recently, I went to see a doctor for ankle pain, and they wanted me to write down my symptoms. They weren’t going to let me type. I could write it in hiragana [simplified Japanese], but it’s easier to write it in kanji—it’s shorter.

Also, within the last two years, I realized that writing helps me memorize and recognize kanji characters. Writing reinforces what I’m learning and is especially helpful for when you have to distinguish between two similar characters.

By the way, you mentioned the JLPT earlier. Did you ever go for N1? [the highest JLPT level]

Amelie: No. I’m thinking about it, but the problem is that I have to memorize all of the remaining kanji that I don’t know. You’re supposed to know over 2,000 characters, and I have no idea how many I know. [laughs].

David: You know, they don’t test you on every single kanji character…

Amelie: I know, I know…

Anthony: But, any of those 2,000 are fair game.

David: I passed JLPT N2 before I knew the 1,000 kanji that could have appeared on the test. It’s only now, two years since I passed the test, that I’ve actually learned those thousand characters. I was able to pass the test by comfortably knowing only 50 or 60 percent of the required kanji characters. You can kind of use your experience to fill in the gap.

Anyway, I like what you both said earlier—that formal training is important for learning Japanese. Every person I met who speaks Japanese well had university training. From that solid base, they were able to improve to reach a certain level of fluency. I think that before you come to Japan it is important to have that kind of training. I went to Japanese language school once a week. Although I couldn’t speak Japanese after that, I was familiar with a lot of the concepts. This meant that later, I was able to start using these concepts much faster.

Anthony: Tell us more about your experience. How did you reach your current level?

David: I think I’m functional in situations that matter to me, so I can manage most aspects of daily life. I’m happy with that because I wanted to be able to live in Japan, which is what I’m doing right now.

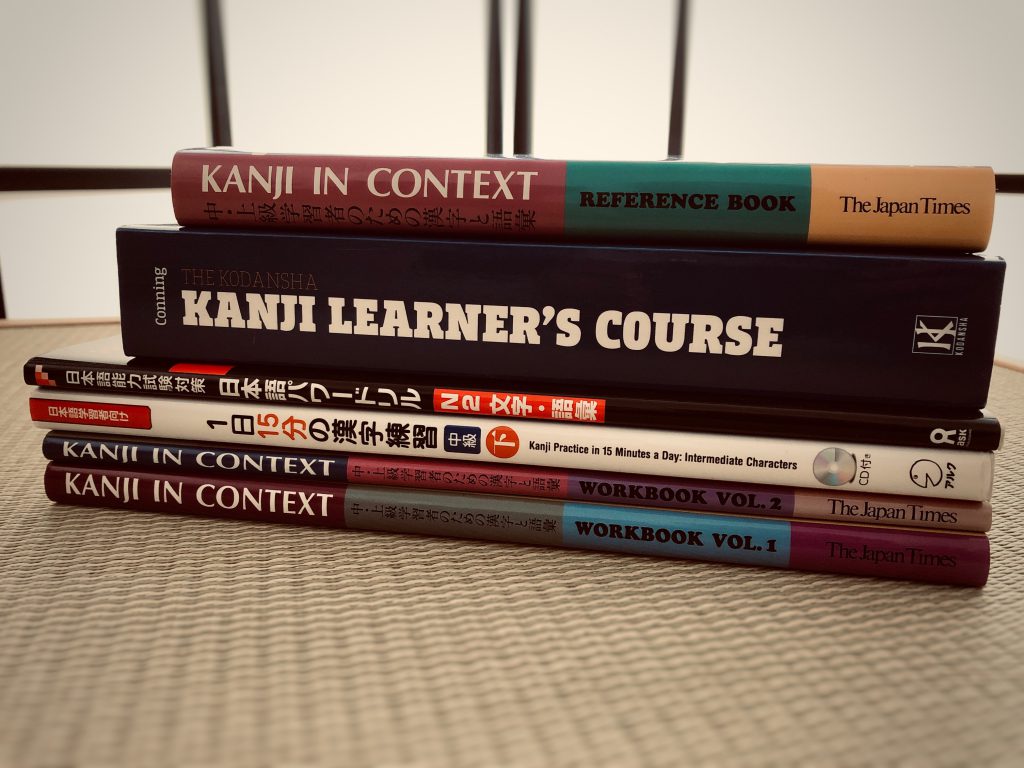

Most of my learning is random. I’ve been trying different things to see what works. We discussed textbooks, but I’ve only found one that I like. Most of them just aren’t useful for me.

Anthony: Which one do you like?

David: J.BRIDGE—but there are only a couple of books in the series. The contents are attractive, built around themes and topics. Most Japanese language books simply push grammar and vocabulary down your throat.

Amelie: Speaking of books, I also have a recommendation. If you want to take the JLPT, the Kanzen Master books are very good. These are good for simply studying Japanese aside from the test—especially their vocabulary books. The lower level books have a lot of pictures and teach words that are related to daily life.

Private Lessons in Japan

Anthony: Any other specific advice for learning Japanese?

David: I was interested in what you said earlier about taking private lessons. I think once you’ve done some formal training before coming to Japan, it’s a good idea to take lessons while you are in Japan as well.

For me, the challenge has been figuring out where to take lessons and what kind I should take. I’ve done daily group lessons—four hours a day, five days a week. I’ve also done private lessons, booking 40-minute sessions whenever I could. I think whatever you do, taking lessons is a good thing. But I’m always wondering if the lessons I take are the best I can get—if what I’m doing is the most efficient way to learn Japanese…

Anthony: I’ve had a few different teachers over the years. It all comes down to the quality of the teacher and whether or not your learning style is a good match with him or her. I’ve tried café lessons as well as an intensive course at a school. You just have to keep trying lessons with different teachers. Look for someone whose teachings can stick in your mind after the lesson. Your teacher should also give you concrete ways to improve.

A lot of teachers out there just go through a textbook with you, doing little more than what you could do on your own. I will say, however, even that method has some value. If you’re like me, you need external motivation—an accountability partner to keep you on track. Just make sure the price matches the quality of your lesson. Overall, there is definitely a difference in quality among teachers, and you may find that you have to pay more to learn from someone who really makes an impact on your learning.

Amelie: That’s one of my problems—I was never able to find a teacher that I was satisfied with. That’s why I learned most of my Japanese on my own. I also felt that if all we were going to do is use a textbook, I could do this on my own, at home, for free.

Digital Flashcards

Anthony: Let’s wrap up with a few more specific suggestions for our readers. I love using technology to learn. So I use the WaniKani digital flashcard system for memorizing kanji. I’ve tried so many different learning methods over the years, and I think that’s the best. I also use Bunpro for grammar. Full disclosure: you can see my testimonial on their website. Additionally, I use Memrise Decks and Flashcards Deluxe for my own vocabulary and kanji content that I pick up on the go.

David: You’re using a lot of digital tools. Do you manage to keep up with all of them every day? They are only effective if you use them on a regular basis.

Anthony: That’s an excellent point. You have to make a personal decision about your pace. Some people just want to focus on learning kanji as rapidly as possible. And if you’re using Wanikani, it’s an intense commitment. You’ll be doing flashcards three times a day to keep up with their recommended pace.

These days, I’m taking a holistic approach. So I practice a little of everything almost every day, but at a much slower pace. So, I’ve been using WaniKani forever, but I’m also studying grammar, reading books, and making my own flashcards alongside it. It’s a slow process, but it keeps my learning interesting. Learning grammar, vocabulary, and kanji together—seeing how they connect—and seeing them in the real world, keeps me motivated.

Amelie: I did try WaniKani to learn some more kanji characters, but I just couldn’t do it. I didn’t take the time every day to do it. It’s probably a motivation problem. I did it for about a week and then it just faded away. It’s a shame…

Anthony: You already know a ton of Japanese. So if you’re happy with your system, you’re good to go.

David: I only use Anki [digital flashcards]. I make my own flashcards based on words I encounter in daily life. I get a lot of words from manga and television series. I find myself creating a lot of new flashcards, and I try to input them in context with full sentences.

Final Thoughts

Anthony: Any final tips for readers who want to learn Japanese from scratch?

Amelie: If you aren’t living in Japan, finding a Japanese person to practice Japanese with will keep you motivated.

David: Combine your interests with Japanese. For example, I love hiking and there are so many opportunities to speak and read Japanese in that context. So, I’m really motivated in that respect.

Anthony: I’ll conclude by saying be realistic about what you can take on, your pace, and your goals. If you are working 40 or 50 hours a week and you have a variety of interests, you need to be realistic about how fast you’re going to learn Japanese. If you’re really busy, it could take several years before you’re comfortable and fluent in the language. So make realistic goals based on your life.