The US Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade in June has turned the spotlight on reproductive and women’s rights worldwide. Under Roe v. Wade, access to abortion was a constitutional right in the US, even if only in theory. Since the draft of the decision was leaked in May, protests across the US erupted around women’s autonomy over their own bodies. The majority of Americans support at least some access to abortion. However, now with Roe v. Wade overturned, women in large swaths of the US are denied or will be denied the basic right to choose to terminate their pregnancies as dozens of states move to significantly restrict, ban, or criminalize abortion. Many Americans are furthermore concerned about the implications for other rights, such as access to contraception, which also relied on Roe v. Wade.

What is the situation of reproductive rights and women’s autonomy in Japan? It’s likewise tinged with politics and patriarchy.

Abortion in Japan

We’ll start with the spotlight topic: abortion. Abortion has been documented in Japan for centuries and was generally permitted until the 19th century. For a large part of history, wealthy Japanese women tended to terminate their pregnancies with abortions, while poorer women had to resort to infanticide (killing the baby after it is born). Although abortion in Japan was officially banned nationwide in 1869, the Meiji government–in power between 1868 and 1912 when Japan started focusing its efforts to mimic Western civilizations–strengthened the bans and criminalized the practice, basing its new policies on French and German Christian doctrinized laws. However, Japan’s bans were not based on religious grounds, but rather largely as political and military strategies to increase the Japanese population (and future taxpayers), receive the approval from Western countries, and make Japan a larger player on the world stage. Nevertheless, despite the risks, abortions and infanticide still continued.

Over several decades, Japanese women and men fought for loosening the abortion bans as well as access to contraception. Activists drafted resolutions for legalizing contraception and abortion in 1934, and these resolutions were referred to after WWII when legislation legalizing abortion was created amid fears of overpopulation. The 1940s and 1950s saw important concessions to legalizing abortion, decades before many other industrialized countries, including legalizing induced abortion (making Japan one of the first countries to do so) and permitting abortions for women meeting certain conditions. Japan was criticized by the West during this period as it attracted foreigners seeking legal abortions from the US, UK, France, and other nations.

While the number of abortions has been steadily decreasing since the 1950s, in 2020, there were about 140,000 surgical abortions. However, scholars believe abortion numbers to be underreported.

Today, abortion is legal in Japan but carries tight restrictions.

For many women, the first major hurdle is Japan’s nearly unique requirement that the male partner gives written consent for her to receive the abortion. (Japan is only one of 11 countries, among Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Equatorial Guinea, that require third-party approval for abortion.) Although the policy is phrased in a way that seems to apply only to married women, unmarried women are also regularly required to submit the male partner’s written consent. This requirement is waived in only limited circumstances, such as inability to contact the partner and “collapsed” marriages (the latter only after a survey found that over 50% of rape perpetrators were former or current boyfriends or spouses). However, these standards are often viewed subjectively. The doctor must approve the abortion, and there have been notable cases of doctors refusing to give legally-protected abortions, including in cases of rape.

If a woman is able to receive both her doctor’s and partner’s approval for the abortion, she must undergo a surgical operation usually within 22 weeks of her pregnancy. The surgery and hospitalization are not covered by health insurance and cost tens if not hundreds of thousands of yen.

The abortion pill, which is used in over 70 nations (and in some has been used for decades), is expected to be approved in Japan this year. It still requires a written signature from the partner. While it is often seen as a safe and cost-effective at-home method of abortion abroad, it is expected to cost about the same as a surgical abortion and potentially require hospitalization in Japan.

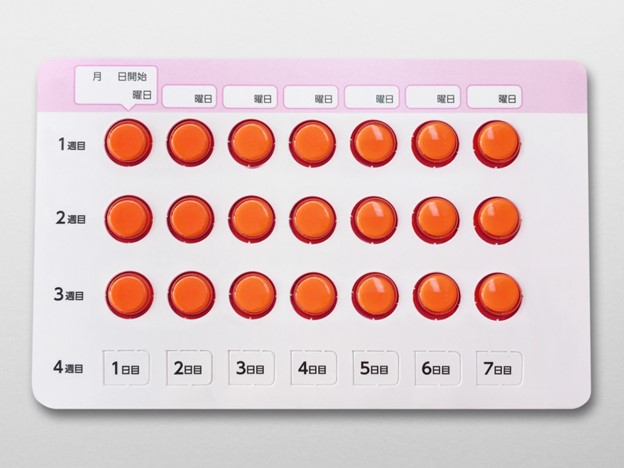

Female Birth Control in Japan

While Japan legalized abortion relatively early, it took 44 years to approve the low-dose birth control pill in 1999. In contrast, the Japanese government approved Viagra after just six months of debate. Insiders claimed that Viagra was approved quickly for safety reasons to the user. Yet, the birth control pill’s approval stagnated for similar “safety” reasons, despite access to relevant data from various other countries. The government also claimed widespread use of the birth control pill could lead to a surge in STIs, yet it showed a marked lack of effort toward improving youth sexual education. Experts say that pressure from abortion clinics likewise slowed the pill’s approval.

Here, it is worth noting that Japan consistently ranks toward the bottom in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Reports. This year, it was rated 116th out of 146 countries, the lowest of both the G7 group and the entire East Asia Pacific region. Japan’s paltry rank is primarily due to women’s low political empowerment and representation. Many experts believe that Viagra was approved in Japan quickly due to the personal interest of the male-dominated government officials. Women’s rights activists and media quickly pointed out the double standards. Doctors also recommended approving the hormonal pill to be used by post-menopausal women who, due to pain and discomfort, did not want to have sex with their partners, who may have now been using Viagra. The birth control pill was approved later in the same year.

Due to years of heavy stigmatization and misinformation, the use of the birth control pill is low in Japan compared to other high-income nations. It is not covered by health insurance and incurs extra expenses by requiring tests and regular checkups. Implants and IUDs are used even less in Japan and are likewise not subject to insurance coverage. Nevertheless, adoption of the pill is increasing, with one small survey finding that nearly 70% of respondents have used the pill before, and about 80% considered using it in the future.

The emergency contraceptive pill has only been available in Japan since 2011. This morning-after pill, which must be taken within 72 hours, is available only with a doctor’s prescription, making it a risky option for many women who may not get it in time, and costing women on average 10,000-20,000 yen. The government announced in 2020 that it would reconsider requiring a doctor’s prescription, but despite civic activism, it has not changed.

Infanticide in Japan

Infanticide has been prevalent throughout Japanese history and has been debated as a legitimate form of birth control. In fact, abortion was legalized in large part responding to serial infanticide. In modern times, infanticide still exists. There were 28 known cases of infanticide of babies less than one-year-old in 2018. To help combat infanticide and support women who do not want to raise the baby, the Jikei Hospital in Kumamoto, a rural prefecture in southern Japan, opened up an anonymous baby drop-off point in 2007. The hospital receives on average one baby a month and also performs anonymous births.

Japan also experiences the phenomenon of “coin-locker babies,” in which unwanted babies are put into public, coin-operated lockers and abandoned. In 1973, a nationwide survey found that 46 babies died that year in coin-operated lockers, and Japan shortened the expiration for coin-operated locker usage that year. This phenomenon inspired some high-profile literature in the 1970s and 1980s. Cases are still intermittently reported.

Final Thoughts

Like in the US, decisions that have the most significant impact on women and girls are largely made by men. Unlike the US, Japan is facing rapid depopulation. The problem is so pervasive in society that I took an entire course about it at university. Rather than access to contraceptives and abortion, this issue is seismically fueled by a lack of affordable childcare options and gender inequality, among a number of other factors such as housing and education costs.

“The discussion really should be about creating a societal system that can support these women more, and destigmatizing women’s access to abortion,” stated Kazuko Fukuda, a reproductive rights leader.

“Women are not the property of men,” Mizuho Fukushima, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, said in parliament regarding the need to obtain the male partner’s written consent to the abortion. “Their rights, not those of the man, should be protected. Why should a woman need her partner’s approval? It’s her body.”

Agreeing with these Japanese feminists, I can’t help but wonder if the hurdles to safe and effective contraception and abortions are again part of the government’s strategy to forcibly increase Japan’s population. However, policing female bodies and viewing them as objects of a political game are violations of fundamental human rights. Trying to make women give birth to babies they do not want or are not ready for is not the way to change society’s behavior. History has shown that it is not a means to an end.