The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines social norms as “the informal rules that govern behavior in groups and societies.” As a country with a famously high-context culture, Japan is known for having an endless amount of unspoken rules that conjure up conflicting feelings of fascination and frustration among foreign visitors and residents.

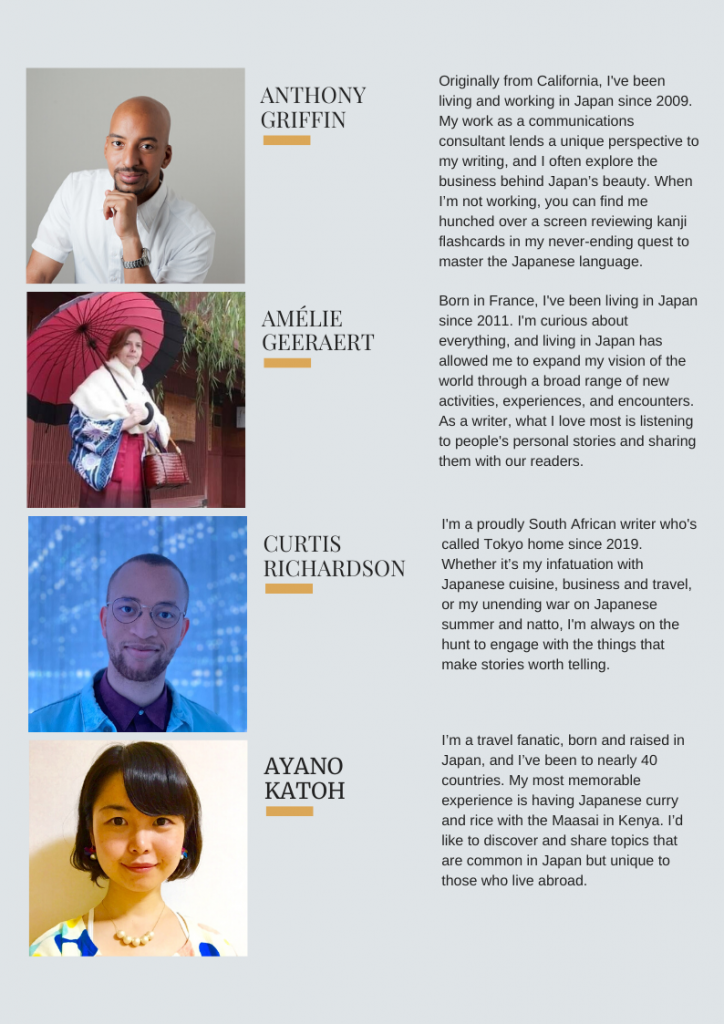

In this inaugural edition of Kokoro Media Unfiltered, we’ll share our diverse experiences with navigating some of the societal norms of everyday life in Japan. This time around, we’re proud to welcome our first guest commentator, Curtis Richardson, a Tokyo-based writer, teacher, and marketer. Learn more about Curtis and the Kokoro Media team in our bios at the end of the article.

Dining Rules: Utensil Use

Anthony: Today, let’s talk about the written and unwritten rules of living in Japan. Who’s ready to share their thoughts?

Curtis: The way I see it, there are two types of rules: career rules and the spoken and unspoken rules of daily life. I’ve struggled more with the daily life unspoken rules, just because there are so many of them. For example, I’m married to a Japanese woman, and her grandparents notice small things about me like how I hold bowls and cups when we’re eating. They tend to wrap their hands around them while I would hold them like drinking glasses. That was one of the unspoken things that I wasn’t prepared for.

Anthony: In that case, let’s keep talking about food and dining rules. Amelie, what are your thoughts? Ayano, do you have any advice for us?

Amelie: If you look on the internet, there’s lots of advice on how to eat with different people. However, there are some subtle things, like Curtis mentioned, that aren’t written anywhere—things that you can only learn on the spot if someone is nice enough to tell you about them.

On the other hand, there are also rules that you can find in books and on the internet that no one actually follows. For example, I was told that when you’re dining at an izakaya [Japanese-style pub] and eating from a communal plate, you’re supposed to use the other end of your chopsticks to pick up food and put it onto your plate. When I did this, people asked what I was doing and told me that no one actually does that. You end up with both ends of your chopsticks getting dirty.

It seems like rules come in different layers. There are obvious rules you have to follow, there are unspoken rules that are difficult to discover, and there are the rules that people made up or just don’t follow.

Anthony: Well, let’s put the chopsticks debate to rest. Ayano, what should we do?

Ayano: It depends. If I have dinner with someone like Amelie, a close friend, we can just use our chopsticks regularly. If I’m dining with people that I’m meeting for the first time, I’ll use a separate set of chopsticks to pick up communal food.

Amelie: Actually, what I was told is not that you change to a different set of chopsticks, but you use the same chopsticks, eating with one end and picking up communal food with the other. However, it seems like no one does that. So, I don’t think it’s a real rule, right?

Ayano: But some people believe it…

Anthony: Curtis, how about you. Have you heard of this rule before?

Curtis: Now that you mention it, I might have seen it once or twice. It always seemed kind of gross…

Amelie: It is!

Curtis: If you do that, you end up touching both sides of the chopsticks. Even though I’ve seen this a couple of times, I never thought of it as a rule. The rules I’ve heard about chopsticks are the obvious ones—don’t treat them like drumsticks and so on. Oh, and there is one more rule! This is a big one: don’t pass food directly from one pair of chopsticks to another. That’s a rule that people need to avoid breaking.

Anthony: Definitely—there’s no mystery or debate surrounding that one.

Curtis: I’ve committed many faux pas when it comes to izakaya dining. Take pouring alcohol, for example. I come from a country and a culture where everybody has their own drink at the table. In Japan, however, it’s all about buying large bottles of beer to be shared with the whole table. This often results in one person pouring drinks for everybody, and when cups get empty, he or she has to fill them up. From what I can tell, it’s usually the responsibility of the person who’s the youngest or has the least seniority. Before I knew this, I would just sit at the table happily drinking away, until someone nudged me and reminded me to start filling glasses.

Anthony: Ayano, can you shed some light on this?

Ayano: Curtis is referring to what I call a follow up drink. Actually, I can’t bring myself to do that—I can’t offer follow up drinks [laughs]. These days young people don’t do this as often as previous generations did. We probably should do it more often, but it’s not as much of an obligation as it used to be.

Amelie: Does it depend on the company you work for? Our company is a smaller company, and perhaps the rules are more relaxed. But if you’re in a larger, older company, are people stricter about this?

Ayano: Yes, it depends on the company. Basically, it has been said that women, rather than men, should be monitoring the follow-up drinks. Perhaps it was associated with femininity. Maybe this isn’t a good topic [laughs].

Dining Rules: Orderly Eating

Anthony: One thing I was told around the time I arrived in Japan was that if you order a teishoku [Japanese meal set], you’re supposed to eat the miso soup last, after eating the main dish, rice, and other side dishes. I didn’t think this rule was a major inconvenience, so I quickly adapted and have been eating that way for years. Eventually, however, people started telling me that I should eat a little bit of everything, not saving one particular dish until the end. On at least one occasion, an observant chef asked me if I didn’t like miso soup. I had to tell him that I was a slow eater and I was just saving it for the end of my meal. So, can we set the record straight regarding this rule?

Amelie: I remember that you had mentioned this before, during one of our meetings, and perhaps it was the origin of this conversation. So, I asked everyone on my team here about the correct way to eat miso soup. Some people said that they didn’t even know that there was a correct way to eat it.

After some research, however, I learned that you’re supposed to have a little soup first, then eat some rice, and then try a little bit of everything else. Then, return to the soup and repeat the process until you’ve finished all of your food.

Anthony: OK. I see…

Curtis: I was told something similar to what Anthony saying. Eat everything, and then at the end, you’ve got about half of your rice left and your miso soup, and that’s when you really get into it. This was reinforced when I first moved to Japan because miso soup was often served toward the end of my meals.

Anthony: So, I’m not alone [laughs]!

Amelie: Ayano, what do you think?

Ayano: Hmm… Maybe you should eat it first… Many people believe that you should eat miso soup first and then move on to the main dish and rice. It’s good to get your chopsticks wet before eating other things such as rice.

Amelie: I read that if you pick up rice first, it will stick to your chopsticks and it might get into your miso soup. That’s not very nice.

Anthony: Well, I guess I need to change my habits. Anyway, we’ve talked a lot about dining, so let’s see if we can squeeze in another topic.

The Unspoken Rules of the Rails

Amelie: In addition to dining rules, there are also many unspoken rules in daily life when you’re on public transportation in the city. You can find a lot of guidance online. For example, you’re not supposed to eat while on the train—even though some people do. However, the way you talk is an issue that is often not addressed. Generally, Japanese commuters tend to speak more quietly than what you might be used to in other countries. So, if you board the train and speak at the volume that you’re used to, Japanese commuters are probably going to think that you are loud.

Curtis: However,I would add that, especially living in Tokyo, there’s a change in atmosphere from the weekday trains to the weekend trains. They go from this very quiet, almost somber, place where everyone is focused on going to work and getting home. Suddenly, Friday night comes along, and the train is bursting with energy. Suddenly, depending on the train line, young people are on the verge of shouting. This was a big shock when I moved here, because I had gotten used to being quiet while on the train.

Amelie: It’s like there’s an unspoken rule that you have to be quiet until you get drunk.

Anthony: Based on my experience, the rule I follow is that in the morning, everyone’s quiet and we should be quiet. But then when you’re on your commute home, after some people have gone out drinking, then it’s okay to be talking and energetic. Any thoughts, Ayano?

Ayano: These days, because of the coronavirus pandemic, people have gotten quieter while riding the train. Now, people try to avoid speaking in public spaces.

Anthony: Good point. But generally speaking, what is your advice for our readers?

Ayano: These days, there are many foreigners in Tokyo, so we can hear many different languages. I’ve gotten used to this, so I don’t think trains sound rowdy. For the record, Amelie and Anthony, I never thought you were loud or rowdy [laughs].

Anthony: What a relief!

Amelie: Maybe that’s because we’ve adapted to the Japanese way of speaking. It’s something we do unconsciously. For example, when I go back to France, I feel that everyone speaks loudly.

Curtis: I think there’s a very low threshold for loudness in Japan. If you compare rowdy people here to where I’m from, they might as well be whispering.

Anthony: Overall, I recommend reading the room. For example, be aware of who’s in the subway car. People will glare at you if you are too loud. So by observing other passengers, you’ll get some good hints as to whether you’re being too loud.

Curtis: I’d like to say that, in and of itself, is a major unspoken rule of Japan. A stern stare is equivalent to a person screaming at you. It means you should stop doing whatever it is that you’re doing.

For example, when I first arrived in Japan, I assumed everyone took their time at ramen shops, sitting down and enjoying their bowls of noodles. So, I would do the same. However, after getting enough stares of death from ramen shop owners, I realized that wasn’t the case. The rule is to eat quickly and move on.

Door Etiquette: The Conflict between Politeness and Personal Space

Anthony: Are there any other topics to consider?

Curtis: One rule that surprised me was that you aren’t supposed to close taxi doors on your own.

Amelie: That makes me think about door manners in general. I don’t know how it is in the U.S. But in France, if you enter a shop and someone is walking behind you, you’re supposed to hold the door for them.

Anthony: Yes, we do that in the U.S. as well.

Amelie: In Japan, based on my experience, about 70% of the time, people don’t do this. I’m not sure why. Maybe they just don’t notice my presence. Regardless, I continue my habit of holding doors, and most of the time I get reactions of surprise from the people I hold doors for, as if I’m doing something very special for them.

Anthony: Ayano, can you give us some insight about this?

Ayano: I agree with Amelie. About 70% of the people I encounter don’t hold the door. However, I believe that at least half of this 70% consists of people that are simply too shy to do so. I hope that’s the case, at least.

Curtis: It seems like holding the door might be an intrusion of personal space.

Amelie: I think that’s a very good explanation. I think this surprises a lot of foreigners because Japan is so often associated with politeness and anticipating the needs of others. So you would expect people to hold the door for you, and it’s easy to be surprised when that doesn’t happen. I think Curtis gave a very good explanation. Perhaps people just don’t want to invade our personal space, and that includes holding doors. It’s like being considerate in a different way.

Curtis: It’s like reverse consideration: I’m considering you by not considering you [laughs].

Anthony: Is that accurate, Ayano?

Ayano: Hmm… Maybe. That might be true for 30% of the people.

Anthony: So, let me ask you this. All three of us like to hold doors for people. Is it OK for us to continue doing so, or is it a cultural faux pas?

Ayano: Please continue doing so. If someone holds the door for me, I think it’s really nice.

Final Thoughts: Watch, Ask, and Learn

Anthony: We’ve talked about a few rules, but we’ve only scratched the surface. There’s so much information out there, much of it conflicting. What final advice do you have for our readers to help them when the rules aren’t clear?

Amelie: Have a look at people around you and observe what they are doing. If that doesn’t work, and you really can’t figure out what to do, sometimes the easiest solution is to ask someone for help directly, despite the language barrier. It’s pretty basic advice, but it’s better than getting things wrong.

Anthony: I agree. Observe and copy. If you can’t do that, don’t hesitate to ask for help. That’s way better than making a huge mistake. Curtis, how about you?

Curtis: That’s good advice. If possible, you should ask specific questions. For example, if you ask a Japanese person if there’s anything you should know before going out to dinner, they might not know what to tell you because going out to dinner in Japan is nothing out of the ordinary for them. So, instead, ask specific questions about chopstick etiquette, how to hold bowls, and so on.

Anthony: Good point. Ayano, can you give us a final piece of advice?

Ayano: It’s impossible to memorize all of the rules before coming to Japan, so just have a positive, open-minded attitude. Show that you are interested in learning about Japanese customs. If you can show that you are doing your best to adhere to the rules, you should be just fine.