It’s no secret that Japanese pop culture, especially video games, influenced me from a young age. In fact, my initial college major was computer science, chosen with the goal of creating my own games.

Unfortunately, by the time I entered college, the initial era of the self-made game creator was a thing of the past. Video games had become big business: a multi-billion-dollar industry filled with multi-million-dollar projects powered by the same massive marketing engines behind the music, sports, and movies. So, I pivoted along with the industry, changing my major to business with an emphasis on marketing. And the rest, as they say, is history.

So when John Wolff, an independent game creator, contacted me via LinkedIn several years ago, I was naturally eager to chat with someone who had lived the dream in the United States and was looking to do so in Japan as well.

We kept in touch over the years and now, back in his hometown of Detroit, Michigan, John recently updated me on his time in Japan and his entrepreneurial journey. In this interview, find out how John first got started, why he came to Japan, and what it was like to work for a Japanese video game company. Read on and you’ll see how John personifies ambition while being savvy enough to realize when it’s best to simply go with the flow. Regardless of where your dreams lie, if you’re looking for inspiration, I’m confident that you’ll appreciate what John has to say.

Video Games as a Gateway to Japan

How did you develop your passion for Japan?

My mother used to run a Kumon center, and Kumon is a Japanese company. It was the only Kumon Center in the Detroit metropolitan area. Because of that, I was introduced to Japan at an early age. I went to Japan for the first time when I was in third grade. So, there was a lot of inertia pushing me toward knowing another language. What brought it home was my interest in video games. I feel like the mecca for video games is Japan. Just look at Mario, Sonic, and all of those games. It made sense for me to take on Japanese from a pragmatic business standpoint. Personally, I think that everyone should know another language, and if I’m fortunate enough to have children, I would definitely impose on them to learn a language of their choosing. Japanese just happened to be the language that matched my initial childhood interest.

Games are beautiful because of their ability to tell stories.

What, in particular, attracted you to Japanese games as opposed to Western ones?

Games are beautiful because of their ability to tell stories. Fantasy worlds and storytelling are seemingly more prominent in Japanese games that have lore, characters, and mythology. My favorite game growing up was Metal Gear Solid, which was made by Hideo Kojima. That was a playable movie. I also loved the Final Fantasy series, as many people do. Final Fantasy games are known for having very deep stories and so much content. That was the appeal. I learned that games, especially ones coming out of Japan, could be other worlds that tell meaningful stories.

When I was enrolled in Bekka [Japanese Language and Culture Program Preparatory Course] at Kansai University, I wrote a paper about how cultural values are reflected in video games. I wrote about kojinshugi, which is individualism, a very classic American sentiment. In Japan, there’s a focus on shudanshugi, which is collectivism. I saw that collectivism was reflected not only in the workplace but also in video games. For example, in Final Fantasy, characters work together toward a certain goal, usually defeating some external threat. Conversely, in western games, you can see kojinshugi reflected in war simulators, which don’t have as deep of stories. Many of them are first-person shooters, where it’s just about one character trying to conquer the enemy and survive. Each kind of game does well in its independent sphere. I’m just more of a shudanshugi person when it comes to video games, and that’s how I came to have an affinity for Japanese games as opposed to games from other parts of the world.

Getting Down to Business

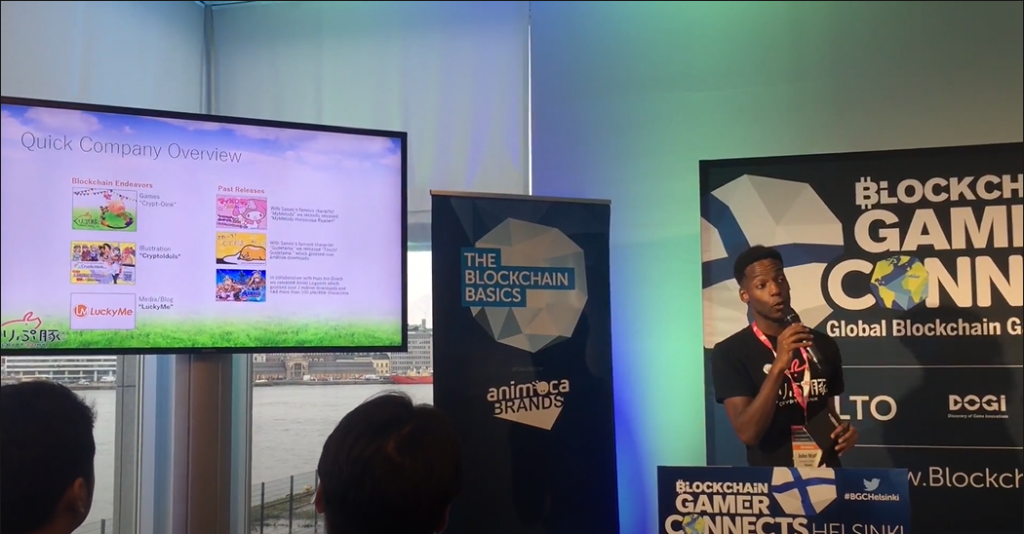

I have to be careful—I could talk forever about Japanese video games and what makes them unique. But let’s switch gears and talk about business for a bit. You started your own company, Urban Electronic Games, in high school. What was that experience like?

When I preordered Metal Gear Solid 3—once again, it all comes back to Metal Gear—I received a copy of Game Informer magazine. One of the cover stories was about learning to make video games, and I was really interested in that. At the same time, my parents critiqued that since I was playing video games all the time, I should try making one. I started to explore this idea and eventually decided I should start a video game company. I actually registered it as a nonprofit. This was just the result of good parenting. My parents said, “We’re not going to buy you a new car, but let’s go and spend $25 so that you can register your company.” That set me on my path.

Actually, being my young self, the first game I ever made was about meeting girls. I also made a game to ask my girlfriend at the time to prom. In college, things evolved, I got more serious, and made some cool titles. Urban Electronic Games, my studio, became my safe haven to learn about the video game industry, and it’s taken me all over the world—Japan and Finland thus far. So that’s how I got started in video games. It’s amazing how long it’s been, and that I’m still working at it.

Working at a Japanese company in general, as you might know, is tough.

What was it like working for a Japanese video game company, in Japan?

Working at a Japanese company in general, as you might know, is tough. I was one of only three foreigners that worked at the company. It was a Japanese video game startup, so it was a unique experience. I was able to have the classic Japanese working experience—working a lot of overtime, for example. However, it was intensified here because video game companies demand even more overtime than typical companies. At first, I was excited to do this, but once we started working those long hours, I didn’t think it was cool at all. In this way, my cultural values clashed often while working there. I’m an American, so I had my expectations about what I wanted for my salary and career path. But at the same time, I was trying to be part of the team in that collective, shudanshugi fashion. Overall, it was a growing experience for both the company and myself. We still collaborate to this day.

I think they saw how they needed to be more international. And I simultaneously saw how I could be more oriented toward the group. I learned how to do a lot with a little, and that serves me to this day.

Frantz Fanon, a black Renaissance writer, said, “To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture.” I believe that, and the same thing applies to international business.

I watched the video about how you crowdsourced and soft-launched your game, WurmZ, in Japan. I was impressed by how you handled business development—how you got out there and directly introduced your game to people. That’s something that a lot of entrepreneurs, especially introverted ones, struggle with. What have you learned about business development and what advice would you give someone who is trying to sell their own product or service?

Passion has to carry you through. Any success that I had in Japan was because I was willing to knock down doors. There’s a nice quote in Beowulf that reads, “Foreign places yield more to one who is himself worth meeting.” Adapt yourself to the culture—don’t fight it. Unfortunately, I met a lot of foreigners who spent too much time complaining about Japan. If you’re on a mission, you don’t have time to be complaining. Similar to what Serena Williams said about being black and being a woman, as foreigners in Japan, we have to work twice as hard to be considered half as good. I’m not a guy who’s obsessed with Japan. I’m not an otaku. I’m pragmatic. I came to Japan with the objective that, by the time I left, I would have released a game and have Japanese connections that could help me in the future. I kept that in my head, and I just kept on working towards it.

I believe that if you’re a real entrepreneur, you’re going to be able to attack what it is that you want. If you’re an entrepreneur in Japan, the onus is on you to learn the language. You can’t break down cultural barriers if you come here knowing only a few words. You have to understand that culture and language are tied together. Frantz Fanon, a black Renaissance writer, said, “To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture.” I believe that, and the same thing applies to international business.

Again, you have to have an attack mentality. We’re not on this earth forever, and I wasn’t going to be in Japan forever. If you’re driven, you’re going to naturally come out of your introverted skin.

A Unique Path to Japanese Literacy and Fluency

Speaking of language mastery, another thing that stood out when we first met was your approach to learning Japanese: taking an intensive program at Kansai University. What specifically did that program teach you about learning Japanese?

I think that anyone who wants to learn Japanese should participate in the Bekka program. It’s pretty intense. They expect you to have passed JLPT [Japanese Language Proficiency Test] N4 before joining the program, and they really want you to have N3. I didn’t have either. They barely let me in the door. The expectations were high, and it was an environment where we only spoke Japanese all the time. It’s basically a program that prepares people to attend a Japanese university. As you know, my objective was to work at a video game studio, so I was trying to learn business-level Japanese. Thankfully, it was all covered there, because they teach using the JLPT prep books. This was a great system because a lot of American colleges don’t use the JLPT books.

We could also take electives that covered specific JLPT questions. This was great practice because to pass the exam, you have to understand how scoring works. You have to do triage when it comes to taking the JLPT and, admittedly, I was a slow test taker. By taking these courses, I could objectively become a better test taker for what was the hardest exam I had ever taken.

Even though the program was so hard—to the point of causing bouts of depression—getting through it really made me grow. So when someone comes to me saying that Japanese is too hard and they can’t learn it, I tell them, “You just don’t want it. I’ve been there, I know what it’s like, and you just don’t want it badly enough.”

Overall, Bekka is a hidden gem that I’m glad I found, and those who really want to learn Japanese should look into it. I don’t believe they have an age limit, because they also prepare people for grad school, and that can be anytime in your life.

However you approach it, learning Japanese requires a lot of effort. Do you think that it’s worth it?

Knowing Japanese gives me an edge in businesses that are relevant to me—video games, for example. I’m now able to localize my games for an entirely new market, something a lot of independent foreign game designers can’t do on their own. If you look at certain KPIs [key performance indicators] such as playtime and money spent per game, Japan has some of the highest metrics in the world. Being able to localize games for this market creates great opportunities.

Final Thoughts on Finding Success in Japan

We’ve covered a lot of ground in our conversation. Is there anything else that you’d like to share with our readers?

If you’re looking for a couple of quick trade secrets, know that Fukuoka is a great place for startups. If you want to crowdfund a project, consider Campfire, which is the Japanese equivalent of Kickstarter.

As for overall advice: don’t resist Japanese culture. If you resist, you won’t have a great experience. Instead, take it all in, and you’re going to find that a lot of opportunities will come your way.