Despite government attempts to increase labor mobility and gender equality, Japan’s labor market remains notoriously rigid. The lifetime employment system is still common and coveted. Obtaining the lauded status of seishain (permanent/regular employee) at an established organization means following a well-trodden path with little room for detours.

Deviate from the status quo, for whatever reason, and you risk being relegated to the path of the perpetual keiyakushain (contract worker), an employment status that typically comes with less job security, fewer training opportunities, limited upward mobility, and lower lifelong earning potential.

Fortunately, Cynthia Usui—author, speaker, and LOF Hotel Management Japan country manager—paints a different picture—one that gives us a glimpse into the future of Japan’s labor market. Born and raised in the Philippines, she came to Japan as a Monbusho scholar and entered the workforce upon graduation. After giving birth to her daughter, she decided to become a stay-at-home mother, exiting the workforce for nearly two decades. In 2011, 52 years young in a country where lifespans are getting longer and longer, Cynthia was eager to do more than simply return to work. She wanted to thrive. To do so, she accomplished a feat unimaginable in Japanese society: overcoming a 17-year gap on her résumé.

In less than a decade, she went from part-time worker to country manager, writing books, making television appearances, and working for prestigious brands along the way. However, her path wasn’t a linear one, and there were major setbacks that punctuated her journey. Cynthia tells this story best, and the details will emerge through the candid conversation that follows.

The Nail that Sticks Out…

You describe yourself as a “multilingual and multicultural professional who has lived, studied, and worked in Southeast Asia, North America, Europe, and Africa.” How has this unique perspective influenced your life and career in Japan?

It’s difficult to find somebody like me in Japan. It’s just a matter of circumstances. Ethnically I’m Chinese, but I was born in the Philippines. I came to Japan to study, I happened to marry a Japanese diplomat, and we moved around every three years. I’ve experienced a little bit of everything, and I’ve been exposed to almost all cultures. So, I can relate to almost anyone that I meet. You can put me in any environment, and I’ll be fine.

I can see this as an asset globally, but we all know the famous Japanese proverb: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.”

I’ve learned to turn that into my advantage. One reason for this is that I don’t look very foreign. I’m an Asian woman, so I’m not very threatening to most Japanese people. Because I speak Japanese, and I’ve lived here long enough, people tend to think of me as Japanese. However, when I do things that are not very Japanese, it’s a lot easier for them to forgive me because, at the end of the day, I’m actually a foreigner.

“Following Your Passion” Isn’t Always the Best Career Advice

At the end of the day a career is like a business. If no one wants to buy you, you can’t really sell yourself.

You are also well known for reentering and thriving in the workforce after being a stay-at-home mother for 17 years. What is your secret to success and what advice do you have for women and mothers in Japan with similar aspirations?

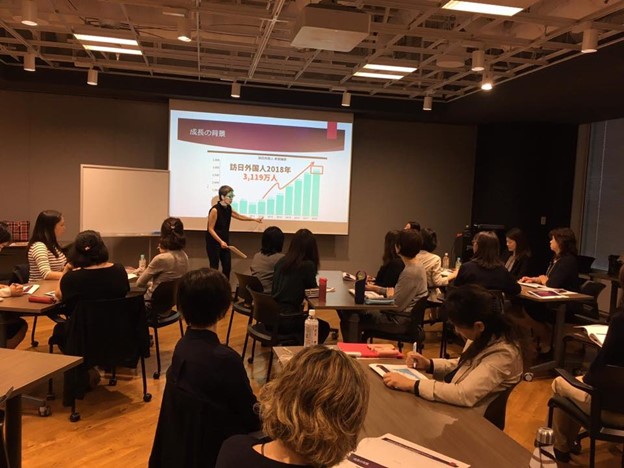

A lot of people talk about following your passion. This isn’t realistic advice, especially for older workers. Only a lucky few can follow their passion and create a career out of that, so I’m realistic. Instead of believing in fuzzy stuff like that, I accepted the job that was right in front of me. I pursued a career in an industry that was growing, and hence it was easier for me to rise.

I started working for a hotel in 2013 when Japan was riding the tourism boom. Imagine if I had gone into finance. My career wouldn’t have gone anywhere because new jobs weren’t being created in that field—there were no new banks, for example. However, in the tourism industry, a lot of hotels were coming up—there was opportunity after opportunity. At the end of the day, a career is like a business. If no one wants to buy you, you can’t really sell yourself. I wasn’t afraid to start from an entry-level position and work my way up.

This is wonderfully practical advice. However, if you’re an older, more experienced person, and you take an entry-level job, sometimes you get promoted quickly, and sometimes your superiors will try to keep you in that position, limiting your growth. How can people rejoining the workforce avoid being taken advantage of?

I was aware of this. I set objectives and deadlines. For example, my first job [after moving back to Tokyo at age 52] at the Tokyo American Club paid 1,300 yen [$16.25] an hour. After I was making 20% to 30% of the sales, I asked to be paid by the month instead of the hour. Instead, they offered me a 100-yen hourly increase. It’s easy to get emotional—mad and resentful—in this kind of situation. I didn’t do any of that. Instead, I analyzed the situation. Because of my performance, they probably wanted to give me what I had asked for, but they couldn’t because they had a set headcount of seishain employees. Unless one of the seishain employees died, there was no place for me. Therefore, I decided to move on from that organization.

You have to be analytical about these situations. In my case, since I was older and had a gap in my résumé. I just took whatever was in front of me and did well. Then, I moved on.

The day that I join a company, I already know that I will be leaving. From day one, I look for transferable knowledge. I always think, “What will I take with me when I leave this company?”

I think the economic gap between the rich and the poor is growing in Japan, and it is polarizing society.

Japan’s Most Important Social Issue

Considering all the conversations you actively engage in on LinkedIn—Japan’s aging society, women in the workforce, and multiculturalism, just to name a few—what do you feel is the most important social issue facing Japan today?

I think the economic gap between the rich and the poor is growing in Japan, and it is polarizing society. This is a huge issue that most Japanese people don’t recognize because they have always believed that everybody is middle class—that everybody is equal. I don’t think that’s the case anymore.

Having people who are seishain—those who have all the job security they want—and those who are not creates a caste system. Additionally, Japanese wages have not gone up. So, there’s another gap between people who are working for gaishikei (foreign-owned companies) and those working for nikkei (Japanese companies).

For example, according to local media, a Japanese elite is somebody in their 30s, working for a major Japanese trading company and earning 8 million yen [$62,700] a year. You know, 8 million yen per year is the salary of the assistant at a large foreign-owned corporation.

Now, we also have people who can work from home. This small, privileged group is just going to get richer. Although this means that more women will have the flexibility to work from home while taking care of kids, this won’t apply to essential workers who are going to be left behind. So, overall, the economic gaps in Japanese society are going to become more and more pronounced.

We’ve seen how this played out in the United States, but what will be the ramifications of a widening income gap in Japan? Will it be similar, or will some uniquely Japanese issues arise?

Japan will have the problems that we see in Europe and the United States, but the process will be slower. The change won’t be as obvious. People are starting to feel this divide, but nobody’s getting angry about it. No one is agitating for change. So, the problems will slowly creep in. It’s like we’re all in this sinking ship, and it’s fine as long as everybody stays on the ship, and we all sink together.

That being said, because of taxation, I don’t think inequality here will be as bad as what we see in other countries. Another reason the situation might not get as bad is because people who are super rich typically don’t flaunt it. Additionally, Tokyo neighborhoods are well mixed, and it’s difficult to determine who is very rich and who is very poor. So, the income divide is still not obvious, at least in Tokyo.

A Second Act: Working in the Hotel Industry During the Pandemic

What inspired you to join a hotel company amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when international travel was restricted and domestic travel was discouraged?

Again, I’m very practical. It was the only thing that was in front of me. Don’t forget that I had been laid off from my job at Coca-Cola when the Tokyo Olympic Games were postponed. So, I had a choice: I could sit at home and continue to fill my days as a supermarket cashier, or I could take this new opportunity. It was that simple.

Initially, I turned the job down. I went out of my way to find fault in the job. Fortunately, even though I turned the job down, they came back to me. While we were talking, I realized that I had turned down the job because I didn’t have the confidence to be at the top of an organization. I had imposter syndrome. Once I realized that, I questioned myself. Several years ago, I was teaching hospitality classes for housewives. Back then, I always thought it would be so cool if somebody with money gave me a hotel, and I could employ the housewives that took my classes. And now, suddenly, somebody with money was offering me three hotels, and here I was turning it down. That was my “aha” moment.

I wanted to create the labor force of Japan’s future, which includes people from different countries and walks of life.

In other words, recalling your hospitality courses helped you overcome your imposter syndrome. Is that correct?

Yes. I realized I was just scared. So, I took the job. I didn’t negotiate the salary. However, I did negotiate for two things: the country manager title and full control over hiring. I wanted to be the country manager because the general manager title was not important enough, and I knew that a country manager title would be more attractive to the media. I was already thinking about marketing, because I was already a known factor in the Japanese media. The story of someone who, in 10 years, went from being a part-timer to a country manager for a hotel company would be more attractive, which could help market a brand that was unknown in Japan.

The reason I wanted full control over hiring was so that I could create a diverse team. I wanted to create the labor force of Japan’s future, which includes people from different countries and walks of life.

Advice for Working in the Hospitality Industry

What advice do you have for non-Japanese people who want to work or start a business in the Japanese hospitality industry?

The hospitality industry is labor-intensive, so it will always need people. If you’re coming to Japan to work in this industry, you really need to learn Japanese. Even if you already have certain skills—digital skills and so on—you still, to a certain degree, need to learn Japanese.

Right now, it can be easy to succeed in the industry because it’s growing and there’s a labor shortage. Eventually, however, this industry will be divided between luxury hotels and basic accommodations. The hotels in the middle will be devastated. Unless you enter the luxury segment, you’re going to be on the basic side of the business. Five or six years from now, there will only be three jobs available at these hotels. There will be my job, the management level below me, and then there will be the housekeeping staff. Technology will replace front desk agents and concierges.

If you are going to be a manager at a basic hotel, you’ll need to upskill so that you can troubleshoot the problems that occur when technology fails. If you are going to work for a luxury hotel, then you want to work on your people skills. You need to be personable in order to provide high-end experiences.

Final Thoughts on an Idyllic Japan

If you could change one thing about Japan, what would it be?

I would love to see less complacency in Japanese society. I’d like people to challenge each other a bit more, asking “why” instead of just immediately accepting something. For example, if someone says, “You can’t use this elevator,” the common response is to just say “okay.” No one ever asks, “Why not?”

When I worked at the ANA InterContinental Hotel, I learned that many Japanese staff members struggled with foreign guests because they always asked “why.” Therefore, the Japanese staff would always have to explain things that typically would have been accepted without question. I wish Japanese people would ask “why” more often as well.

Conversely, what is one thing that you hope never changes?

The one thing I would never change is the insane amount of honesty in Japanese society. If you ever lose anything in Japan, it’s almost always returned to you.

Is there anything else that you would like to convey to our readers?

If you’re somebody looking to settle in another country, come to Japan. It’s really a land of opportunity, especially when you consider the declining population. A smaller economy doesn’t necessarily equate to a poorer one.