If you’re moving to Japan (or even taking an extended vacation), you’ll want to start learning the language, including how to read. Register for a class or buy a coursebook. You’ll start first from hiragana, then katakana, and finally kanji. It’s a natural progression.

Actually, it’s not. Or at least, not for everyone.

Hear me out. If you’re a serious student of Japanese learning outside of Japan, this flow makes absolute sense. This is because the bulk of Japanese can be written in hiragana. With hiragana, you can write anything you don’t know the kanji for and almost all of Japanese grammar. Every sentence in Japanese will feature hiragana. On the other hand, katakana is used significantly less, mostly for foreign loanwords (about 18% of the language), certain common words with kanji that can be too complicated to read and write, or onomatopoeia.

But as an English-speaking immigrant, being able to understand these loanwords will be immensely and immediately useful. In fact, an estimated 90% of the 45,000 loanwords in Japanese come from English. Once you understand the patterns of the language, you’ll essentially have an instant vocabulary bank.

Katakana Examples

Katakana words permeate all levels of Japanese, from basic shopping items to complicated chemical structures.

For example, you may go to the store to find:

- バナナ (banana, “bananas”)

- オレンジ (orenji, “oranges”)

- チキン (chikin, “chicken”)

- ラーメン (raamen, “ramen”)

- パン (pan, “bread,” from Portuguese “pão”)

- オニオンパウダー (onion paudaa, “onion powder”)

- ハンドソープ (hando sopu, “hand soap”)

- ペーパータオル (pepaa taoru, “paper towels”)

While some of the above have a native Japanese word that may be alternatively used, all of these words above are commonly used and written in katakana.

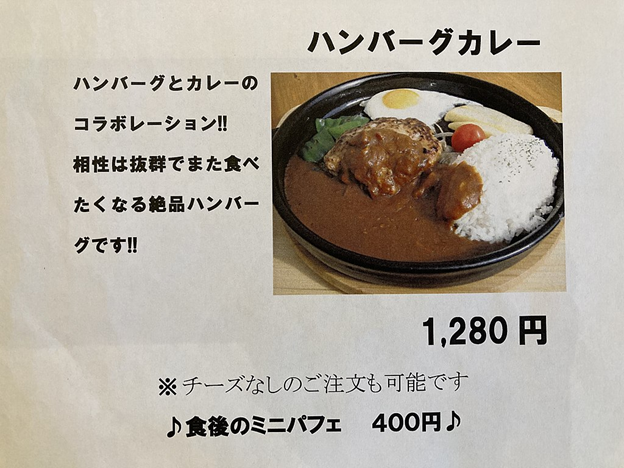

Just in this photo, we see a lot of katakana words:

- ハンバーグ (hanbaagu, hamburger steak)

- カレー (kare, curry)

- コラボレーション (koraboreshon, collaboration)

- チーズ (chiizu, “cheese”)

- ミニパフェ (mini pafe, mini parfait)

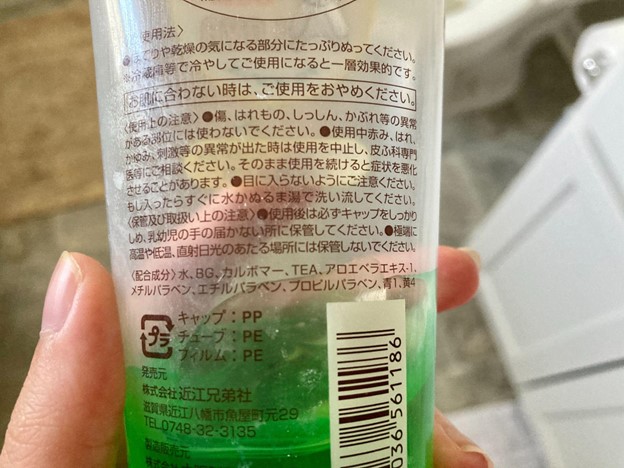

Here’s another type of example. This is an aloe rub I purchased. Let’s take a look at the ingredients:

- カルボマー (karubomaa, carbomer)

- アロエベラエキス (aroe bera ekisu, aloe vera extract)

- メチルパラベン (mechiruparaben, methylparaben)

- エチルパラベン (echiru paraben, ethylparaben)

- プロピルパラベン (puropiru paraben, propylparaben)

Half of the ingredients are written in katakana. If your skin is sensitive to any of them, you’ll know what to look out for.

Therefore, if you can understand katakana loanwords, you will have an automatic vocabulary. Here, I’d like to present to you a guide on how to demystify katakana words taken from English and how you can put your katakana knowledge to immediate use.

Limits on Japanese Pronunciation Changes English Sounds

What are the rules for creating katakana words? Let me tell you.

(Note: If you are unfamiliar with how to pronounce Japanese, Tofugu has an excellent guide.)

With the exception of double consonants–the “kk” in gakko (“school”), for example–as well as “n” (and sometimes “m,” depending on romanization methods), Japanese consonants always need to be followed by a vowel. Most of the time, that vowel is a “u,” or an “o” after a “t” or “d.”

Therefore, the Japanese-ified version of the English word “sun” turns into サン (san). On the other hand, “sum” and “hum” would become サム (samu) and ハム (hamu), respectively. “Monday” would be written as マンデー (Mandee–no “u” sound after “n”), and “Wednesday” would be ウェンズデー (Wenzudee–with an “u” after “z”). “Hat” would be pronounced as ハット (hatto), with an “o” sound after the “t.”

Japanese also has no distinction between “l” and “r” sounds like English does. Therefore, the English words “read” and “lead” pronounced in Japanese would both be リード (riido), and you will need to understand which it is by context. However, when there is an “r” in the middle of the word before a consonant in English, Japanese usually mimics it using a long vowel. With any “l” or “r” with a vowel after it, Japanese typically uses ラ (ra), リ (ri), ル (ru), レ (re), or ロ (ro). Therefore, “homework” would be pronounced as ホームワーク (homuwaaku), while “homeless” would be ホームレス (homuresu). “America” transforms simply into アメリカ (Amerika).

We see almost all of these rules played out in “McDonald’s.” McDonald’s in Japanese is マックドナルド (Makkudonarudo). We can see an “u” sound after the “k” and “r,” but an “o” after the final “d.” The “l” turns into a ル (ru).

When reading katakana words, a little bit of reverse engineering can go a long way. Once you are used to the rules and patterns, you can even try making your own katakana words. When in doubt, if you don’t know a word, see if you can katakana-ize it! It may just be understandable.

Watch Out for False Friends, or Wasei-Eigo (“Japan-Made English”)

Learners beware: not all katakana words are what they seem. Japanese has plenty of “wasei-eigo,” which literally means “Japan-made English.” These are words that originally came from English, but Japanese has altered them significantly.

Sometimes, if the English word is too long, Japanese will cut off the middle or end to form a new word that is easier to pronounce. Common examples are:

- パソコン (pasokon, “PC”–from “personal computer”)

- テレビ (terebi, “TV” –from “television”)

- コンビニ (konbini, “convenience store”)

- チョコ (choko, “chocolate”)

We also saw this with エキス (ekisu, “extract”) above.

Some katakana words have been taken from English but mean something entirely different in Japanese. Examples are:

- コンセント (konsento, “power outlet”–not “consent”)

- カニング (kaningu, “cheating [on a test]”–not “cunning”)

- マンション (manshon, “condominium”–not “mansion”)

- ハンドル (handoru, “steering wheel”–not “handle”)

- バイキング (baikingu, “buffet”–not “Viking”)

Some wasei-eigo takes multiple English words to make new meanings in Japanese.

Some examples are:

- ベビーカー (bebii kaa, “stroller”–literally, “baby car”)

- テレビゲーム (terebi gemu, “video game”–literally, “TV game”)

- バックミラー (bakku miraa, “rear-view mirror”–literally, “back mirror”)

- フライドポテト (furaido poteto, “french fries”–literally, “fried potato”)

- アメリカンドッグ(Amerikan doggu, “corn dog”–literally, “American dog”)

Final Words

Starting with hiragana is logical if you are building up your Japanese proficiency. With hiragana you will be able to read and write more sentences while practicing your grammar and vocabulary. However, if you need immediate survival Japanese, learning katakana should be your priority.