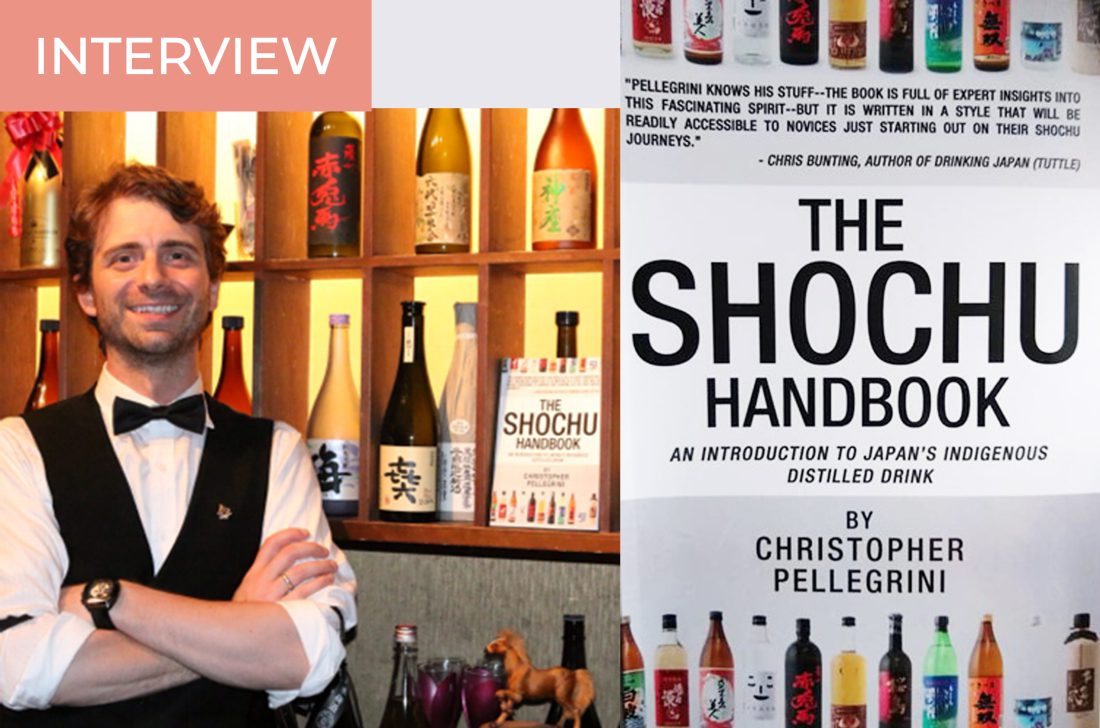

This article is particularly exciting for me because I had the opportunity to chat with one of the world’s leading authorities on shochu, Chris Pellegrini.

A Japanese spirit evangelist, Chris is passionate about spreading the gospel of shochu and awamori. He made a convert out of me!

From talking shochu 101, to clearing up the differences between shochu and Korean soju, we cover a lot of ground in this interview. Read on to discover the exciting world of Japan’s indigenous spirit. Who knows? By the time you’ve finished reading you might be ready to jump down the rabbit hole.

This article was kindly provided to Kokoro Media by Yamato Magazine and was originally published on their website in April 2020. This interview is part of Yamato Magazine’s “The Kokoro Files,” a series of articles that share the stories of people and their connection to Japan. Autor: Jamie Ryder.

Yamato Magazine is a Japanese culture publication based in the UK. Through long-form articles and interviews, it champions Japanese mythology, mental health, food, and drink.

The magazine also helps Japan-inspired brands grow through copywriting and content marketing. Services include article writing, website copy, social media, and newsletter building.

Thanks so much for taking the time to talk Chris. It’s been great learning about shochu through your role on the Sake on Air podcast.

For anyone who doesn’t know what shochu is, what makes it different from other alcoholic drinks, and why should more people be drinking it?

Completely my pleasure. For those who don’t know? Well, I’d start by saying that shochu (and awamori) are Japan’s best-kept secrets. And we’re not talking about a fad here, or something that was recently cooked up by a crafty ad company like the pop group du jour.

This is centuries and centuries of history that connects the archipelago from Okinawa in the south to Hokkaido up north. Shochu is made in every prefecture of Japan, but it has only recently gained wider recognition as Japan’s native spirit.

Due to its inherent diversity of aroma and flavor, it’s difficult to compare it to just one other spirit category from another part of the world. But I guess we can start by saying that it is an intensely artisanal product that is single-distilled and retains much of the character of the ingredients that were used to make it. To offer a more concrete definition: (honkaku) shochu is a spirit distilled from approved ingredients and their koji.

I know that sounds really simple, but it is quite possibly the most complex spirit on the planet. It’s also surprisingly difficult for many people outside Japan to pronounce correctly. Shochu is pronounced like the two English words ‘show’ and ‘chew’ tied together.

One of the things that stands out about shochu to me is the huge variety of ingredients that are used to create it. Can you explain the differences between honkaku shochu and other versions like korui shochu?

That was one of the things that originally drew me to honkaku (premium, authentic) shochu—it can be made with dozens of ingredients and there are thousands of brands to choose from and compare.

Honkaku shochu is the traditional and flavourful style of shochu, and the most popular ingredients in terms of sales in Japan are sweet potato and barley. Other major types include rice, soba, sesame, and kokuto—a rich, caramel and molasses-forward type of top quality Japanese brown sugar that is melted and added to the second stage of fermentation.

Every type of honkaku shochu described here is distinct from every other ingredient type because of the type of still that is used to produce them, a traditional pot still. And even more importantly, honkaku shochu is distilled once in a pot still, an exceedingly rare quality in global spirit traditions. As a result, we often end up with is a bottled product with a lower alcohol content, but also orders of magnitude more flavour and aroma retained from the fermented ingredients. Typical ABVs hover in the 25-30% range, but shochu can legally be bottled at up to 45% ABV. Anything higher, however, cannot legally be labeled as honkaku shochu.

So honkaku shochu, and this is the majority of shochu enjoyed by people living in Japan, is usually a mid-ABV spirit that tastes like what it is made from. People have long enjoyed it mixed with hot water, but many brands sip smoothly on the rocks, with a bit of cool water added, or cut with club soda. At home in Japan, awamori and shochu are before, during, and after meal beverages much like beer and wine, but there’s another type that is a much more recent invention and mirrors vodka in a few ways.

Unfortunately, it is also legally called shochu, but it is mass-produced, multi-distilled, aroma-neutral, and generally used as the alcohol in chuhai and other simple cocktails at izakaya in Japan. It’s rarely consumed on its own.

When people talk about shochu as a category, they’re almost never referring to this low-proof vodka substitute, and unless you are a fan of citrusy chuhai, then you’d probably never have cause to buy it. The quality and tradition in the category is the monopoly of honkaku shochu, the original shochu that spirits and drinks fans the world over are just starting to learn about. I truly wish that the newer sub-category, officially known as korui shochu, would change its name to help avoid confusion!

I also find the subtle differences between shochu and its cousin awamori to be fascinating. What makes awamori its own distinct breed of alcohol?

Great question. Awamori actually predates shochu, and it is made in Okinawa Prefecture, a string of islands linking Amami (southern Kagoshima Prefecture) and Taiwan. It was originally inspired by imported spirits from other parts of Asia with many historians pointing to Thailand as being a likely source.

Awamori used to be made from a variety of ingredients, but these days it is only made from rice. And when I say rice, I mean long-grained rice from Thailand. This is likely a holdover from centuries of trade across Southeast Asia which the Ryukyu Kingdom (now known as Okinawa Prefecture) played a major part in.

As awamori production ebbed and flowed over the centuries, and competition increased once production restrictions were eased in the 1800s, it eventually produced the style that we now recognise as awamori today—a 100% single-distilled rice spirit that is made from a single, all-koji batch fermentation.

Another important caveat is that the koji must be made with black koji-kin (mold spores) rather than white, which is more common in shochu production, or the yellow koji-kin which is used in nearly all saké production.

If you make awamori according to these rules in Okinawa Prefecture, then you can label it as “Ryukyu Awamori,” a geographical indication (also referred to as an appellation) that is protected internationally by the WTO like champagne is. While shochu has three international appellations of its own, it is generally not handcuffed by quite so many rules as awamori.

With regard to flavour profile, if we compare a “standard” awamori with a “standard” rice shochu, then you’ll likely notice that the former has earthy and grainy notes while the latter is more floral and lighter. This is due not only to differences in ingredients (rice type, yeast strain, and koji), but also to still type.

Awamori is most often made in a pot still that performs distillation at atmospheric pressure, while what we think of as “standard” rice shochu is usually distilled under reduced (vacuum) pressure. Atmospheric distillation creates a hearty, vigorous boil which causes alcohol and many other organic compounds and esthers to vapourise and escape from the still. Vacuum distillation, on the other hand, allows the fermented mash to boil at a much lower temperature which results in a softer and sometimes fruitier spirit. The alcohol vapours, and everything else floating up into the swan neck of the still, are then exposed to cold temperatures and condensed into shochu or awamori.

When was the moment that you fell down the shochu rabbit hole and decided you wanted to turn it into a career?

Oh wow. I don’t know if there was necessarily one specific moment, but I can recall a few tipping points over the past couple of decades.

The first, of course, was an experience in a bar when the bartender tasted me through about five different types of shochu, long before I could really speak any Japanese. I was taken aback by the diversity of the drinks I was offered, all of them referred to as shochu.

Then there was the joy I got from learning about these drinks firsthand through trips to various distilleries around Kyushu Island and Okinawa. I used to brew beer in the US, so I was easily able to understand and connect with the folks working in those tiny old family-run distilleries.

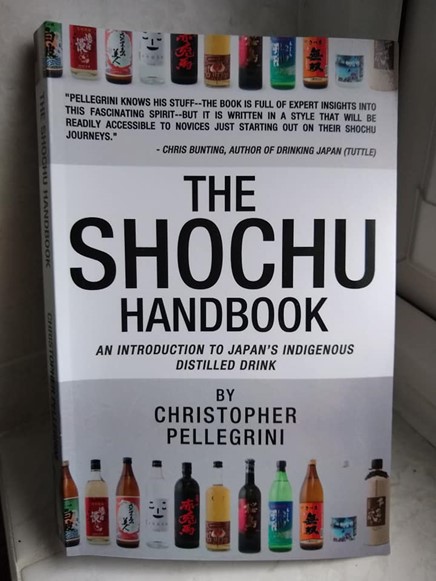

I eventually ended up writing ‘The Shochu Handbook’ as a way to celebrate all of the small distilleries in Southern Japan while also allowing me to potentially reach a larger audience with everything that I had picked up over years of hands-on learning.

You have the distinction of being the first person to be certified by the SSI as a shochu kikisakeshi in Japan and a shochu advisor by the SSA in America. Did the training differ between courses or were they similar?

They are quite different, mostly in terms of scope and depth. The Shochu Advisor course is basically an English language introduction to the Shochu Kikisakeshi license which is offered in Japan. The advisor course and test cover about one tenth of what’s in the kikisakeshi exam, and one important element that is missing is a blind tasting.

Having said that, it’s currently the best way to familiarise yourself with the category if you’re looking to acquire a certification and you’re not ready to take a written test in Japanese. That was the biggest challenge honestly. The Shochu Kikisakeshi test, an exam in four parts, mostly felt like a foreign language test to me. That whole experience probably took a couple of years off my life.

Having read your very insightful book, I found it interesting about the mention of there being three major shochu booms. What factors do you feel have led to the most recent boom?

The most recent boom was around 15 years ago and was largely thanks to folks in Japanese metropolises figuring out that the overall quality of the category had progressed, in leaps in bounds, over the preceding 20+ years.

We’re talking about significant improvements in cultivation and harvesting, ingredient preparation techniques, fermentation, distillation, and aging. Pretty much everything really.

Just focusing on sweet potato shochu, a sub-category that has the widest spectrum of aroma and flavour, the innovation and development of potatoes specifically suited to the production of shochu was a major catalyst. And then you also had distilleries that were going to far greater lengths to ensure the quality of potatoes before they even began the fermentation process. The fermentation process itself was fine-tuned to make sure that aromas were more balanced and less aggressive than they’d been for years.

Having become such avid consumers of whisky and brandy, it made sense that the complexity and variety inherent in honkaku shochu piqued people’s interest here in Tokyo, and also in Yokohama and Osaka.

The proliferation of cask-aging in the shochu industry has of course appealed to whisky fans, even though current tax regulations prevent extended aging–anything barrel-aged longer than around three years would likely be too dark to tax as honkaku shochu. But you could easily see why people became attracted to it. Incidentally, it was during that time period just after the turn of the century that domestic shochu sales overtook those of saké.

It feels very easy for people to get confused between shochu and the Korean drink soju. So, let’s help clear that up. Why is shochu different than soju?

Honkaku shochu and Korean soju shouldn’t even be in the same sentence if we’re being honest. Their names rhyme, but the similarities pretty much end there.

They are as different as sweet potatoes and yams, which are often mistaken for one another but don’t even belong to the same family (sweet potatoes are part of the morning glory family while yams are related to lilies). I don’t know…maybe that isn’t the best analogy because plants are grown and spirits are made, so let me just cut to the chase.

The vast majority of Korean soju is factory-produced, watered-down vodka with sweeteners added to it. Soju is incredibly cheap to produce and also extremely affordable for the end-user. It’s typically chilled and served communally both during and after a meal, and in Korea it is consumed at pace in what are essentially shot glasses.

Another common way to drink it these days is to pour a measure of it into a glass of Korean lager, a simple cocktail often referred to as somaek (so– from soju and –maek from maekju which is Korean for beer). Taking it a step further would be to just drop the entire shot, glass and all, into the beer. This is called poktanju (poktan means bomb and ju means alcohol in Korean).

Multi-distilled drinks like soju and vodka are convenient because no matter what you make them with, the result after dilution will taste pretty much the same. As we’ve discussed, this is the exact opposite of what can be expected when making honkaku shochu. And this makes perfect sense because of a few crucial points that differentiate it from soju, vodka, and many of the world’s spirit traditions.

First, honkaku shochu is distilled once in a pot still which means it smells and tastes like what it was made from. Second, no additives are allowed. That’s Japanese tax law right there. If you put sweeteners, colour stabilisers, or adulterate the alcohol in any other way, then it’s no longer classified or taxed as shochu. Third, most shochu is made by small to medium-sized companies using high-quality ingredients and labour intensive methods.

And these methods are tried and true. They’ve been developed over centuries and some, alongside Ryukyu Awamori, are recognised and protected as regional specialties. Satsuma Shochu is the geographical indication granted to sweet potato shochu made with locally harvested spuds and koji in Kagoshima Prefecture.

Barley shochu made with a rice-koji primary fermentation made to the right specifications on one island in Nagasaki Prefecture can be called Iki Shochu. Rice shochu made in one mountainous region of Southern Kumamoto Prefecture is Kuma Shochu.

At the risk of putting too fine a point on it, honkaku shochu is made to exacting standards in a decidedly old-school manner which allows very little margin for error. On the other hand, most soju is designed to be sweet and cheap.

I’ve heard that one of the major reasons for the confusion between the two drinks is because of the liquor control tax loophole in the States. Especially in California. If the legislation changed, do you think that could have a positive impact on the shochu industry?

That’s 110% correct. Yes. Some shochu makers have taken advantage of a licensing loophole in California that allows 24% ABV (and lower) spirits to be sold on a so-called soft license (what most restaurants have) which allows the sale of fermented beverages such as wine and beer.

If you print the word ‘soju’ on the front label, then sushi restaurants and other izakaya that don’t have a full-blown bar license can still sell your products, and that’s where the confusion sets in.

It’s seeded by the shochu makers that lazily do this, and it’s incredibly short-sighted. When consumers in California pick those bottles up, they see both ‘soju’ and ‘shochu’ on the label. It’s confusing, and a large percentage of Americans think that soju and shochu are one and the same.

And as many reading this article have probably discovered, when you’re out drinking soju, you often end up imbibing more than you probably should. There’s a ton of people out there who have had lost mornings and afternoons due to a few too many green soju bottles, and that experience ends up preventing people from even trying shochu. I’ve heard it half a million times through meeting tourists in Tokyo.

Unfortunately, the mislabeled shochu bottles don’t just stay in California. The same labels are used on bottles that end up getting shipped to other states as well. I’m originally from Vermont, and there’s a state liquor store in Burlington that has a half dozen shochu brands, several of which have soju fraudulently printed on the label even though the same soft license loophole doesn’t exist in my home state.

It’s a huge own-goal, and new legislation is desperately needed. I love the fact that a relatively low- to mid-proof spirit is available on a soft license, but there needs to be more labeling flexibility to avoid misinforming the public.

What types of shochu would you recommend trying for people who are just staring their journey into the industry?

You know, it depends on where they’re coming from alcoholistically. Is that a word? It is now.

Barley shochu appears to be easy for people to get into because beer and whisky are omnipresent around the world. However, there are myriad directions we can go in here.

For red wine drinkers I might suggest a sweet potato shochu made with something from the “beni” family. These potatoes are generally purple or red, and the resulting shochu mixes sweet and tart in a way that’s reminiscent of tannins.

Saké drinkers will easily understand rice shochu which is home to a lot of fruity aromas such as green melon, banana, and apple. White wine lovers would probably also be comfortable starting with rice shochu. Anyone who enjoys rice shochu but wants more complexity should search for atmospheric distilled brands or swim south to Okinawa where awamori awaits them with open arms. Oh, and awamori aged extensively in clay can take on some lovely vanilla highlights. You can thank me later.

Tequila drinkers will definitely want to start in sweet potato (imo) territory. While it may sound like you’re in for something sweet, most imo shochu is only lightly so. The aroma spectrum is impossibly vast thanks to nearly infinite production variables, so we can find everything from smoke to lychee, straw to raisin, conifer to yogurt, and everything in between. It’s absolutely bonkers.

Kokuto shochu is an easy choice for rum drinkers, and I would recommend soba (buckwheat), shiso (perilla), or chestnut shochu for anyone who just wants to jump right in but would appreciate sure footing when they land.

By the way, if you don’t mind whiskey, then reach for any shochu that has a golden hue. If it’s honkaku shochu, then it means that it’s been barrel-aged for a bit, and I refer to it as “diet whiskey” because of shochu’s surprisingly low-calorie count and the elegant vanilla, cherry, and oak influences that present themselves.

Drinking shochu and awamori on the rocks is standard, but I’d also suggest adding a bit of cool water to create what is commonly enjoyed as a mizuwari mix. You can experiment with the ratio, but 50:50 is often a safe bet. Adding club soda has recently become very mainstream in Japan, so that’s a good way to go as well, particularly with something that’s a little on the sweet, floral, or fruity side of the spectrum.

Me? I’m an oyuwari kind of nerd. I generally drink my honkaku shochu cut with hot water. Even in the summer.

If there was one thing you could change about the shochu industry, what would it be and why?

Ooh, that’s a good question. One thing, huh? Well, I think I’d wish for the good people of this culture- and tradition-bound industry to adopt a more long-haul way of thinking.

Awamori distilleries, shochu distilleries, saké breweries—pretty much everybody needs to lend a hand to creating new markets, and I’m talking about focusing on international consumers here. Such a change will necessarily entail teamwork, and by that I mean working together with one’s domestic rivals. That’s a tough sell for a lot of these companies. They have some impressive history with their rivals, and it’s hard to just ignore that narrative at the drop of a hat.

But the awamori and shochu industry will find success overseas more quickly if we get buy-in from producers large and small, and by that I mean expending resources in a way that not only promotes their respective brands, but also focuses on teaching the world about Japan’s little-known spirits.

What’s your best advice for anyone who would like to become a shochu sommelier?

There’s a distinct paucity of information about awamori and shochu, even in Japanese, so I have a very good understanding of how difficult it can be to get started here. First and foremost, you need to taste. You need to develop your palate, and start to learn how wide and long the playing field is for aroma and flavor. It’s all about developing your vocabulary.

I’m not just talking about awamori and shochu here. Learn about wine, learn about mescal, learn about curry, and learn about tropical fruit. Drive with the windows down. Ground aroma in context and attach concrete vocabulary to it whenever possible.

My next piece of advice probably goes without saying, but I’d also recommend getting your hands on every bottle of awamori and shochu that you possibly can. I’ve been based in Tokyo since 2002, so I’ve accumulated a decent number of labels which are now stashed all around the house.

I’d say that you definitely need to have experience with as many brands as possible, and you also need to drink those shochu and awamori every which way. Try them on the rocks, mizuwari, oyuwari, straight, cut with club soda, everything. The industry here in Japan is half-convinced that the world needs to start drinking awamori and shochu alongside dinner, so you should learn to appreciate where they are coming from.

However, keep in mind that there are thousands of brands produced every year, so this process is anything but a sprint. Furthermore, there probably isn’t another category of spirit that has as much aroma and flavour diversity, so take your time getting to know regions and styles. I highly recommend that you take tasting notes and go back to them the next time that you have the opportunity to sip the same spirit.

Do you feel a fourth shochu boom is coming or are we already living in it?

It has yet to transpire. I believe that the fourth shochu boom will take place outside Japan. It’s going to take a lot of work, and a lot of resources, but I’m confident that we’ll be hearing the word shochu pronounced correctly all around the world by the end of this decade.