When it comes to learning Japanese, there are deceptively simple questions that most teachers struggle to answer. For example, “What is the difference between the particles wa and ga?” Or, ”Why is this word typed without kanji?”

When I saw that Yuki Nivez, founder of Bow & Arrow Language, was succinctly answering some of these tough questions via her social media content, I took notice. As I started writing more and more about my own language learning journey, I thought it would be a great idea to join forces and interview Yuki to bring even more language learning tips to our audiences. Thankfully, she agreed with this idea, and I’m grateful to bring you her thoughts on entrepreneurship, language learning, and Japanese culture. By the end of this interview, you’ll have new tips and insights to help you successfully learn, live, and work in Japanese.

Providing Lessons with Precision

What is your entrepreneurial journey? How did you become a self-employed language instructor?

When I used to work in a language school that was run by a large corporation, I sometimes felt frustrated with the limitations of complying with their regulations, especially when they didn’t align with the students’ best interests. During new student level assessments, I was sometimes pressured to put them in classes that were not the most suitable in order to maximize teacher and classroom utilization. There were also times when I felt designated curriculums and textbooks were not well suited for some students.

After I left the school, I came up with the idea of an onsite lesson service. By having lessons at clients’ workplaces, I wouldn’t need to have a physical location. This would eliminate the need to maximize classroom utilization and so on. I could focus on the thing I actually care about: teaching. This matched the demand in the market and I was fully booked within my first year of going solo.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, it affected many businesses including my clients, and I lost all of my corporate contracts. Some of them closed down their Tokyo offices and some of them issued layoffs. The ones that survived initiated major cost cuts, and Japanese lessons were one of those cuts. Everything happened in a matter of a few weeks.

Now I do most lessons online and, despite my earlier concerns, they are just as effective as teaching in person.

A few weeks after I thought I lost everything, the people I used to teach at those companies started contacting me, telling me that they wanted to continue our lessons, even though costs wouldn’t be covered by their employers.

This experience made me grateful and motivates me to provide quality lessons. Now I do most lessons online and, despite my earlier concerns, they are just as effective as teaching in person.

Japanese is often said to be one of the most difficult languages to learn, but that’s only half true.

How does your work relate to your passion for Japan? What motivates you to do what you do?

When I say that I teach Japanese to businesspeople it’s often misinterpreted as teaching business Japanese. However, what I actually teach is Japanese as a second language, at all levels.

Many of my clients are beginners and, in fact, I enjoy teaching beginners the most because of their reactions in their first lessons. Japanese is often said to be one of the most difficult languages to learn, but that’s only half true. Japanese does have complex elements such as honorific and humble speech, counters, and kanji, etcetera. These things tend to get more attention because of their uniqueness. However, the basic—and essential—part of the language is surprisingly simple! When I introduce and explain how Japanese works, people are astonished by its simplicity and how logical it is. That’s one of my favorite moments.

Top Tips for Learning Japanese

It’s important to remember that Japanese is a language with its own vocabulary, grammar, and structure—it’s not a translated version of your native language.

What are your top tips or hacks for aspiring Japanese learners?

It’s important to remember that Japanese is a language with its own vocabulary, grammar, and structure—it’s not a translated version of your native language. Sometimes, you might not find the exact equivalent of the expressions you are used to saying in your language.

One of the things I’m often asked is how to say “it depends” in Japanese. Yes, this is such a useful expression but, in Japanese, you have to indicate what “it” depends on.

For example, you have to say “it” depends on the person: hito ni yoru [人による] Or, when “it” depends on the situation, you say: jokyo ni yoru [状況による].

The closest match for “it depends” would probably be toki to baai ni yoru [時と場合による], which means “it depends on the time and the situation.” Another option might be sono toki ni yoru [その時による], which means “it differs each time.”

When I explain this, people usually understand. However, I occasionally get a frustrated reaction such as “But I just want to know how to say ‘it depends!’” It is frustrating not being able to use the expressions you’re used to, but as you adjust to indicating what “it” depends on, speaking this way will become natural.

instead of trying to find the exact translation of what you would say in your native language, it’s important to learn and accept Japanese as it is.

Here are some additional examples. When expressing sympathy, we don’t say “I’m sorry to hear that.” Instead, we use taihen desu ne [大変ですね], which means “that’s tough.” Instead of saying “good luck” as you would in English, we say ganbatte [がんばって] which loosely translates to “go for it” or “do your best.”

So instead of trying to find the exact translation of what you would say in your native language, it’s important to learn and accept Japanese as it is. On the bright side, there are so many useful expressions unique to Japanese like shoganai [しょうがない ], which means “it is what it is.” This can be used in a positive way to say “it’s no one’s fault” or “let it go and move on.”

My favorite is do desho ne or do desu ka ne [どうでしょうね/どうですかね], which can be used to answer a yes or no question without saying yes or no. I really wish this expression existed in English too [laughs]!

Don’t worry too much about making technical mistakes like using no incorrectly. Generally, people will still understand what you are trying to say.

What are some common mistakes that Japanese learners make and how can they be avoided?

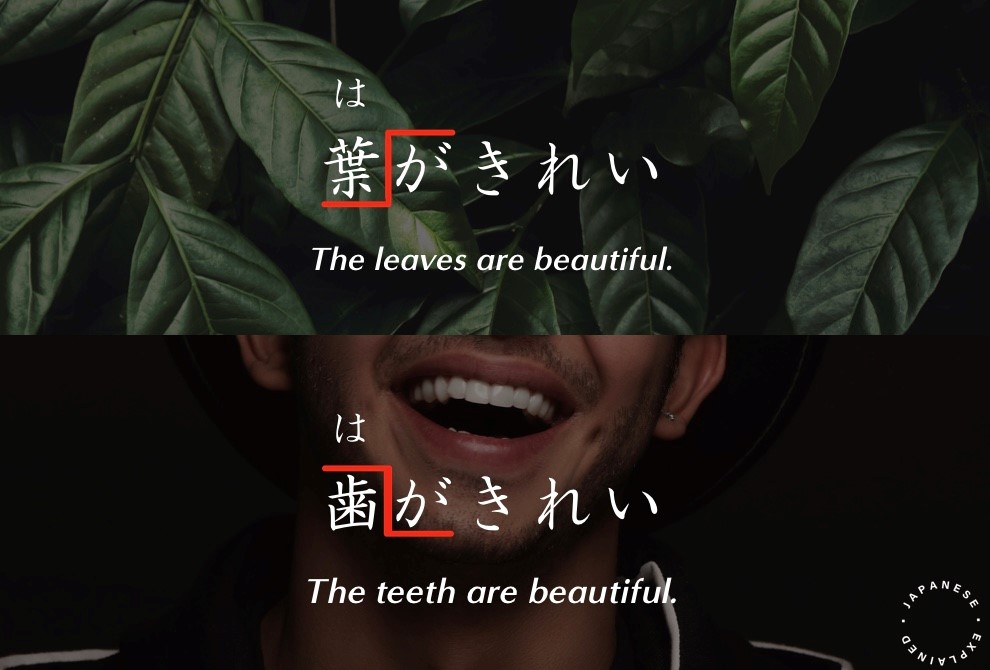

Here’s some technical grammar advice: Do not add an unnecessary no [の]. This particle is used to connect two nouns. For example, when saying watashi no bagu [わたし の バッグ ], which means “my bag,” no connects “me/my” and “bag.”

However, many learners at different levels use no when they don’t need to, such as between an adjective and a noun. For example, we can’t say “interesting book” by saying omoshiroi no hon [おもしろい の ほん]. Instead, we need to say omoshiroi hon [ おもしろい ほん].

That being said, don’t worry too much about making technical mistakes like using no incorrectly. Generally, people will still understand what you are trying to say.

What would you say to expats who believe that learning Japanese isn’t worth the time or financial investment?

If having more opportunities in the job market and being able to communicate with people aren’t motivating enough, it’s a scientific fact that learning a new language can boost your brain!

Beyond the Classroom

Most non-native learners start with the polite form because it has a much simpler conjugation system. However, native Japanese people do not notice that and think the plain form is easier.

If you could change one thing about the way Japanese is commonly taught to non-Japanese learners, what would it be?

This is more about how native Japanese speakers act around Japanese learners, but I often hear how uncomfortable learners feel when they speak Japanese and native speakers giggle and say “kawaii” [cute]. I know that they have no bad intentions and only mean well, but this can discourage learners from speaking.

Also, Japanese people tend to speak to beginner-level learners using plain-form Japanese [tameguchi] instead of the polite [desu/masu] form. This too is done with good intentions. This has to do with the different language learning processes between native speakers, who acquire the language naturally as children, and non-native speakers who are acquiring Japanese as a second language. Most non-native learners start with the polite form because it has a much simpler conjugation system. However, native Japanese people do not notice that and think the plain form is easier because that’s how children speak. But in fact, the plain form is much more difficult for beginner-level learners.

Yasashi Nihongo [やさしい日本語], also known as Easy Japanese, is a system that was introduced after many non-native Japanese speakers faced difficulties accessing information about lifelines and shelters at the time of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. This language guideline is now used in NHK news reports for non-native Japanese speakers. However, it is still not widely known by Japanese people. I hope awareness about this increases soon.

Using indecisive words might seem unprofessional or irresponsible in other cultures. However, in Japanese society, using direct, decisive language could be seen as arrogant or uncooperative.

In my experience, learning Japanese efficiently requires an understanding of Japanese culture. What cultural differences should we take into account when English speakers learn Japanese, and how do they impact the learning process?

My clients often say, “Why do I hear desukedo [ですけど] so much at work? I know it means ‘but’ or ‘though,’ but it feels like every sentence ends with it.” This is because desukedo has many functions other than “but” or “though,” and one of them is to soften requests and statements. This expresses politeness and shows that you are not taking things for granted.

Learners also often wonder why Japanese people use the word tabun [たぶん], meaning “maybe,” a lot during meetings. I hear things like, “If I kept saying ‘maybe’ at meetings in my country, I would be kicked out of the room.” Using indecisive words might seem unprofessional or irresponsible in other cultures. However, in Japanese society, using direct, decisive language could be seen as arrogant or uncooperative.

Tatemae [one’s publicly displayed stance] and honne [one’s true feelings] are sometimes overemphasized when highlighting cultural differences. It is true that Japanese people tend to avoid direct confrontation and conflict, and this affects how people speak. However, in reality, these concepts are universal in human society, to some extent. White lies and ghosting exist in any other country and culture. It’s best not to read too much into it. At the end of the day, we are all human!